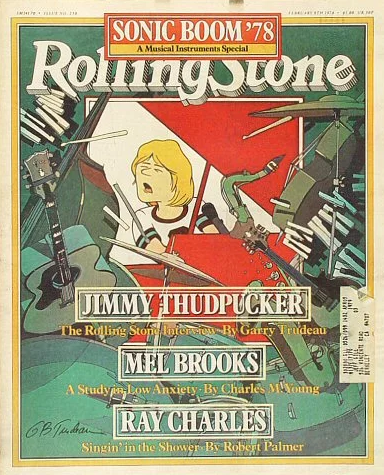

Doonesbury’s resident rock’n’roll legend Jimmy Thudpucker first made the cover of the Rolling Stone in September 1976, featured in an illustration for an article about the growing relationship between corporate rock and electoral politics. In February 1978, Thudpucker again graced the RS cover, this time as the subject of an “interview” (penned by Garry Trudeau) to promote the release of his new Greatest Hits album. The interview explores two essential themes. First, Trudeau uses Thudpucker’s voice to poke fun at the music and musicians that were the magazine’s bread and butter (appearing in a special issue dedicated to recent developments in musical instrument and studio technology perhaps guaranteed an even higher industry readership than usual). Beneath that, the interview is an extended reflection on how a generation that “came of age with youthful rage at My Lai” struggled to reckon with a deeply traumatic collective experience of war, resistance, and violence. The role of Jimmy’s music in that period, and in the ensuing reckoning, is also a prominent theme of the liner notes for the Thudpucker LP, also penned by GBT. Let’s dive in.

Jimmy joined the Doonesbury cast in September 1975 when Zonker sat in on one of his recording sessions. Thudpucker’s interest in topical material – he recorded songs about the Mayaguez incident, his wife’s campaign for the state legislature, and Mo Udall, an Arizona Congressional representative who’d opposed the Vietnam war – made him a natural choice to produce a song and later stage a benefit gig for Ginny Slade’s Congressional run. From there, Thudpucker became a regular member of Doonesbury’s supporting cast, typically as a mouthpiece for GBT’s observations about the rock music that was becoming more and more central to American identity as the Boomer generation became the arbiters of American popular culture.

A key theme in Jimmy’s longer story is the question of the relationship between art and commerce, and how the commercialization of rock diluted the spirit of the music. In one 1975 strip, Jimmy croons the copyright notice for the album he’s recording, a nod to how commercial considerations are deeply woven into his art. The producer later tells Jimmy he can book off for the evening and leave the rest of the work to studio players. “Oh Lord,” the rocker laments. “Whatever happened to playing together?”

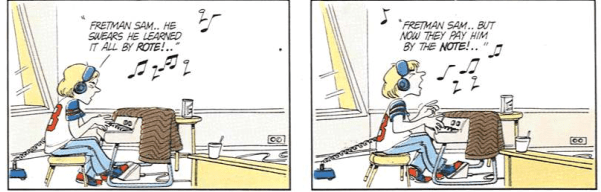

Jimmy has deep respect for the pros who played the parts that turned his compositions into mega-hits, and he laments how monetary considerations had undermined their art. Thudpucker’s Doonesbury appearances feature nods to several prominent real-life studio players, including guitarist Jay Graydon (Dolly Parton, Ray Charles, Steely Dan, Marvin Gaye) and bassists Dennis Parker (Tom Jones, Johnny Mathis) and Donald “Duck” Dunn (Booker T. and the MGs, Eric Clapton, Otis Redding). One of Jimmy’s biggest hits was “Fretman Sam,” which Trudeau describes as a “thinly-veiled tribute to the legendary session-man ‘Wah-Wah’ Graydon.” The song revealed Jimmy’s disdain for “artists who minimize the contributions of studio musicians.” Jimmy laments how artistry had been reduced to commodity: “Fretman Sam. He swears he learned it all by rote. Fretman Sam. But now they pay him by the note!” “Fretman Sam” builds on a moment when Graydon revealed the extent to which monetary concerns guided his approach to his craft. In November 1977 Jimmy was confronted with the extent to which “Wah-Wah” had cynically adapted to the realities of playing corporate rock. Graydon – wearing a “Fretman Sam” t-shirt – “[works] up an estimate” for performing his part, advising Jimmy that the song has “a lot of quarter notes,” which will be expensive: the tune has “over a hundred bars … with about eight notes a bar. At $2.75 a note…”

When Jimmy expresses his dismay at Wah-Wah’s mercenary approach, the guitarist defends himself: he has to “charge by the note” because “cats were takin’ advantage” of him.

Jimmy’s Rolling Stone interview gave Trudeau space for an expanded critique of the effects of corporate money on the rock world. We’ve already seen how Rick Redfern’s stint at People and Zonker and Mark’s trip to Studio 54 showed Trudeau mocking how 1970s celebrity culture saw marginally-accomplished people being celebrated just for the sake of being famous, not for any sort of enduring accomplishment. As an insider, Thudpucker sees that world for what it is: a place where status is doled out, and revoked, arbitrarily. In the music biz, Jimmy reflects, “a legend is usually no more than someone with two consecutive hit singles.” That dynamic feeds a cruel public fickleness, however: an artist may be “a fucking pillar of the industry,” but inevitably the day comes when “they’re carting you out the back door.”

Jimmy goes on to take down some of his peers, often in pretty harsh terms, for embracing the superficial, materialistic culture that had grown around their work. “The only thing standing between” rockers and “total illiteracy”, he observes, was their “need to get through their Mercedes-Benz owner’s manuals.” Mick Jagger, who by the late 70s had become a regular in the society pages, is a target of Jimmy’s ire: he notes that it was impossible to “open a paper … without seeing a picture of him at some film opening cooing into Baryshnikov’s ear.” When Margaret Trudeau, wife of Canada’s former Prime Minister (…and mother of our current PM) was spotted partying with the Rolling Stones at a Toronto nightclub, Jimmy sarcastically observes, she was the one “accused of social climbing.” Thudpucker also sees some profound moral failure in the rock world. Roughly a year after hanging out with Bob Dylan at his Malibu home, Jimmy disavows his friendship with the man, noting that he saw Dylan as a hero “before he got into wife beating.”

Jimmy’s not airing grudges and dirty laundry just to be provocative: his comments are part of a larger critique about how rock betrayed core values in its transition from a soundtrack to youthful rebellion to corporate product. The guy who wrote “Street-Fighting Man” being on the regulars’ list at swanky nightclubs seems like a breaking point for Jimmy, a sign that rock had lost all relevance, even as artists attempted to perpetuate the activist impulse of earlier times. Even Jackson Browne, Thudpucker’s closest equivalent here in consensus reality and a mainstay on the progressive benefit-gig circuit, gets taken to task for his earnest commitment to incorporating social justice into his work in a way that ultimately lacks authenticity: “There is a point,” Browne’s comics-page doppelganger maintains, “in which a lament becomes a whine.” Times had changed, and the work rock musicians had done to advance progressive politics a decade earlier seemed less relevant in more cynical days. Thudpucker told Rolling Stone that was considering staging a Rolling Thunder Revue-style tour with some of his contemporaries, but he really wasn’t sure if audiences needed “another stage full of old lefties jerking off to the tune of ten dollars a head.”

As Jimmy reflects on where rock was in 1978, he looks back a decade prior, when those “old lefties” helped shape a dynamic culture that emerged against the backdrop of, and in opposition to, America’s war against the Vietnamese people. By the late 1970s, the Boomers were beginning to come to terms with the trauma of the Vietnam era. This reckoning was reflected in the broader culture: The Deer Hunter came out in 1978; Apocalypse Now, a year later. Both the Rolling Stone interview and Trudeau’s liner notes focus closely on Jimmy’s role in the anti-war movement, and his work chronicling the aftermath of those terrible years.

The Grateful Dead played for the protesters at Columbia in 1968 and at an anti-war rally at MIT the day after Kent State. Jimmy too lent his talents to the movement. On 15 November 1969, Jimmy Thudpucker joined Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, John Denver, and Peter, Paul, and Mary in DC to perform at the Second Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, an anti-war protest that brought an estimated 200,000 (some claim as high as 500,000) people to the capital three days after journalist Seymour Hersch first reported on the My Lai massacre. According to Rolling Stone, Jimmy’s performance of “I Do Believe” (the only rock song to ever win a Pulitzer, much as Doonesbury was, in 1978, the only comic strip to do likewise) “electrified” the crowd and “went on to become the anthem for an entire generation.” Trudeau describes how Jimmy’s performance was the precursor to the police violence that erupted at the end of the protest, describing how the song had a “galvanizing effect … on a nearby unit of the National Guard.”

Much of Jimmy’s work explores the legacy of the war and the movement against it. Trudeau’s liner notes describe “Ouverture ‘73” as neither “J’accuse or mea culpa,” but “as eloquent a post-mortem on the war in Indochina as could be found anywhere on the music scene.” Thudpucker sees the song as “an ode to the cacophony of public dissent,” but the way the song was recorded speaks to a desire on his part to incorporate the experiences of the men who fought the war into that dissent, a sentiment that brings to mind the work of figures like John Kerry and Operation Dewey Canyon, a 1971 protest that saw members of the newly-formed Vietnam Veterans Against the War throw their medals onto the Capitol steps. Thudpucker wanted “all the musicians to be Vietnam vets,” because they had been “damaged” and “had a lot to say.” Jimmy tells Rolling Stone that one of the players, pianist David Foster, had “lost a couple of fingers at Khe Sahn, but could “play the meanest keyboard this side of Leon Russel.”

Here in consensus reality, Foster is Canadian and did not serve in Vietnam, but Thudpucker’s choice to highlight musicians who had experienced the war foreshadows a later project that featured a similar approach. In 2001 avant-garde jazz violinist Billy Bang released an album titled Vietnam: The Aftermath, which included titles like “Yo! Ho Chi Minh Is in the House” and “TET Offensive.” Billy Bang served in Vietnam, and the album was recorded by a band made up of fellow Vietnam vets. A follow-up release, Vietnam: Reflections, incorporated Vietnamese musicians into the ensemble.

I’m writing this as media commentators rush to compare the current student protests against Israel’s war on Gaza to Vietnam-era anti-war activism. Then as now, protesters risked a range of consequences when the state decided their protests had gone too far. Men facing conscription into an unjust war burned their draft cards and left behind loved ones and futures, fleeing to Canada and elsewhere. Muhammad Ali went to jail; four college kids died at Kent State. While Jimmy didn’t have to deal with anything that heavy (…to borrow a phrase from the times), the popularity of “Ouverture ‘73” brought state power down on him. He recounts how after the track went gold, “A whole van of G-men turned up at [his] accountant’s office” and “tore the goddamn books apart.” (…it turned out that he was actually due a refund from the IRS). The fallout from “Overture ‘73” wasn’t the only time that Jimmy faced consequences for his antiwar stance. He tells Trudeau that his song “Fuck General Westmoreland” earned him a place on a second version of Nixon’s infamous Enemies List (this one maintained by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare), one made up exclusively of figures in the arts, including Donald Sutherland, Philip Roth, and the Jefferson Airplane.

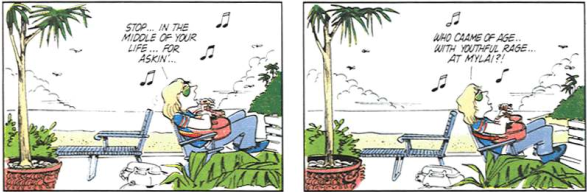

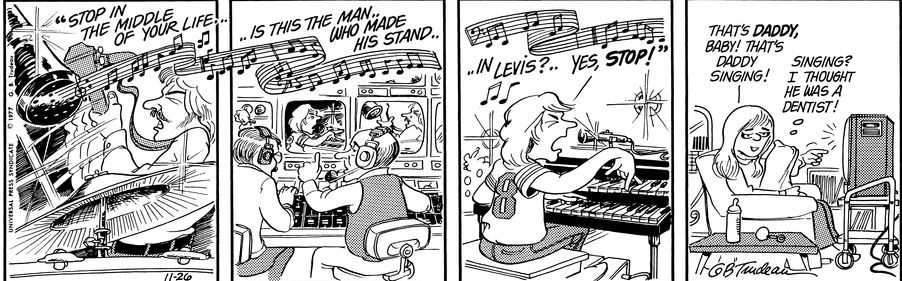

In the strip where Wah-Wah Graydon works up an estimate for his part, the sheet music he’s holding is for “Stop,” a Thudpucker classic featuring the immortal lyric “Stop in the middle of your life for askin’: Who came of age with youthful rage at My Lai?” As much as Jimmy’s music is tied to the movement against the war, his most poignant tune is about the long reckoning with a period that saw political, racial, and social divides, an unjust and increasingly unpopular war, and a crook in the White House threaten the stability of the United States unlike any other time since the Civil War. Trudeau describes the song as “a wrenching lament of a close friend’s failure to integrate the concerns of another era with his new, mellow lifestyle.” The tension between the upheavals and violence of the Vietnam era and the lifestyle trends of later years is a driving dynamic in the longer Doonesbury narrative – to name only one relevant moment, sometime in the 90s Jimmy was gigging at a bar in Ho Chi Minh City popular with Vietnam vets vacationing in (or going on a sort of pilgrimage to, or both) the country where they had fought.

As the journalist Laura Miller notes, “the debacle in Vietnam, the paroxysms of the counterculture and the menace of nuclear war fomented an apocalyptic mood” among a generation of people moving into middle adulthood. You don’t have to be as cynical as Uncle Duke to know that there’s money in the kind of generational pain that war and civil upheaval can produce. The 1970s – the “Me Decade” – witnessed a growing popularity of “self-help” movements like Rolfing, EST and Transcendental Meditation. These supposed pathways to healing, or self-actualization, or to whatever made-up psychobabble term sounded marketable, were sold to a generation that was increasingly looking inward as they sought to come to terms with the mass trauma of their youth.

Like the Coca-Cola “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” ads, many of those therapeutic approaches nodded at counterculture values while encouraging individual consumption. Thomas Harris, author of I’m OK, You’re OK asserted that healing one’s own trauma was a precursor to fixing wider social and political woes: “The problems of the world … essentially are the problems of individuals. If individuals can change, the course of the world can change.” Yet while advocates of the various self-help movements that came to the fore in the wake of the paroxysms of the 1960s often framed individual healing as something that would contribute to the greater good, Miller sees a naivete at play. This naivete is at the heart of the conflict that “Stop” chronicles: a “mellow lifestyle” can’t possibly ease the trauma of a bloody war. The self-indulgent and superficial nature of the “mellow lifestyle” became a central target for Trudeau during the post-Vietnam era. Mellow guru Dr. Dan Asher frequently appeared on Mark’s radio show, promoting new approaches meant to help people achieve a desired “mellow” state of being but were in reality just new consumer fads.

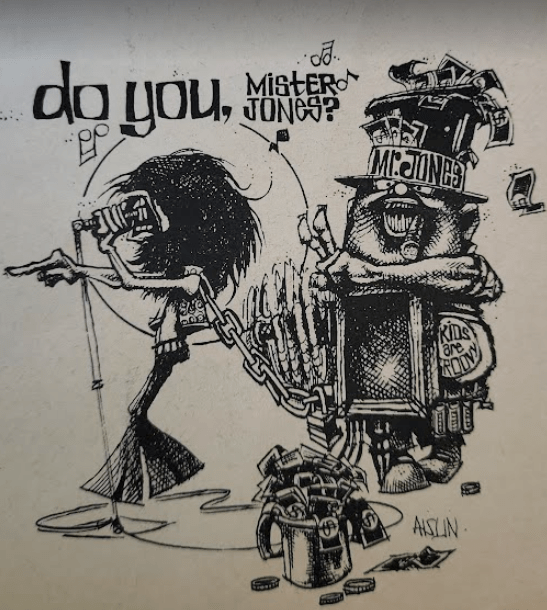

The cynicism at play in the Self-Help Seventies wasn’t new: it was, to a certain extent, rooted in the co-option of the counterculture by corporate capital a decade earlier. There’s an old cartoon by the Montreal cartoonist Aislin that perfectly captures the dynamic between protest music and the corporate establishment. A rocker is singing Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man”: “Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones.” In the last panel, we see the singer is chained to an organ grinder who’s been raking in the dough; his hat reads “Mr. Jones,” and he’s wearing a button that reads “Kids Are Groovy.” As Jimmy tells Rolling Stone, the Moratorium, a key moment in the resistance to the war, quickly became another way to sell product to the youth market. When Columbia Records president Clive Davis saw the dramatic after-effects of Jimmy’s performance of “I Do Believe,” he immediately capitalized on the opportunity. In Jimmy’s telling, Davis “saw the riot on the six o’clock news, and by seven, the masters were on their way to Los Angeles. Forty-eight hours later, before the last of the demonstrators had even made bail, the single was in the stores.”

The Rolling Stone interview isn’t the only time where we see Jimmy looking back on the past with a wiser, more critical eye on his experience of the Long 1960s. A strip from November 1977 – right around the time Trudeau would probably have been drafting the Rolling Stone piece – shows Jimmy leafing through some old lead sheets in preparation for a television appearance; he comes across “I Do Believe.” “Boy does it seem dated,” he tells his wife, who notes the song’s simplicity, especially its “baby chord changes.” “Can you believe this was once an anthem for an entire generation?” he replies.

I don’t write much about Garry Trudeau’s drawing. I don’t know anything about cartooning to begin with, and my interest lies in tracing the Doonesbury narrative and putting it in its historical, political, and cultural contexts, not to do straight-up comics criticism. One Thudpucker strip, however, stands out visually from anything GBT had done previously. Jimmy’s November 1977 television debut on Midnight Special is executed with a dynamism that Trudeau had never really engaged in previously. The close-up drawings of Jimmy and Wah-Wah Graydon allow for an intense expressiveness that stands in marked contrast to Garry’s typically more subtle approach. The way the lyrics move across the panel boundaries is also unusual for the times and gives the strip a dynamism that stands out sharply in a title known best for being really static – to the point where Trudeau was often accused of using photocopies in strips that featured four identical drawings of the White House. The Midnight Special strip foreshadows a more energetic approach Trudeau would explore after his early-1980s sabbatical.

You can tell GBT had fun drawing that strip, and I venture to guess that as a music fan, he’s had a lot of fun with all of Jimmy’s appearances. Maybe a particular affection for Jimmy led GBT to give him a backstory that runs far deeper and is more detailed than just about any other character in the strip. Admittedly, much of that backstory is alluded to more than detailed – the preface to the interview mentions a “tragic boating accident” that Thudpucker had been involved in three years earlier, leading to a number of lawsuits. That said, Jimmy exemplifies a synthesis of Trudeau’s twin goals as a cartoonist, namely to tell great stories with compelling characters while engaging in social and political satire. Trudeau used the Rolling Stone appearance and the album’s notes to situate Thudpucker at specific, crucial moments of a history that is central to the longer Doonesbury narrative: the Vietnam war, resistance to that war, and the still-incomplete, decades-long reckoning those moments brought about. Scott Sloan’s repeated references to his presence at key 1960s moments like Watts, Selma, Kent State and Chicago root him in that same history, but not with the kind of vibrancy that these more extended textual formats give Jimmy.

Next time out, we’ll get back to Jimmy Carter’s White House tenure and start setting up a key moment in Doonesbury history: Duke’s alleged “death” at the hands of the Iranian Revolution.

Stay tuned.

It is funny how I took some characters seriously, and others lightly.

Zonker, Joanie Caucus, Duke I took those characters as serious vehicles to present a point of view.

I looked at Jimmy more casually.

Note that I am not claiming that Jimmy carried less meaning, I am just relating how I related to the character at the time.

My Rock goes Hollywood canonical example at the time would be Cher and Gregg Allman.

Plus it was the era of the instant block buster.

Frampton Comes Alive seemed to come out of nowhere and just dominate, for the whole summer. Only to be replaced by Boston dominating immediately after.

Rock was weird and getting weirder, for sure.

LikeLike

Oh, yeah. Everything you read in this post is new to me. I feel like l really cracked something open here in terms of how l understand the strip.

Thanks as always for reading!

LikeLike