Our last look at Doonesbury in the Carter years ended just after Jimmy Carter’s inauguration, with Zonker and his friend Nemo the Begonia discussing the new president’s political navieté. Nemo saw Carter’s campaign stump-speech touchstone about wanting to lead a government that was as unselfish and kind as the American people as a sign of Carter’s innocence: “the whole reason government exists,” Nemo observes, “is that people are not inherently unselfish and kind.” Meanwhile, on his way to a Georgetown affair in honor of the new president, Dick Davenport pointed out a contrasting characteristic of Carter’s: a deep political cynicism, revealed in how he ran as a political outsider but ultimately appointed a Cabinet made up of “cronies, retreads and tokens.”

In the weeks that followed, Garry Trudeau leaned hard into the idea that Carter was ultimately more committed to the political symbolism that defined his campaign than he was to bringing meaningful change to DC’s political culture.

On 2 February 1977 Jimmy Carter delivered his first televised address to the nation since taking office. Evoking the memory of FDR, another Democrat who came to power in the context of prolonged national crisis, Carter gave a “fireside address”; unlike Roosevelt, whose radio talks predated the television age, Carter’s wardrobe considerations were a factor in setting the tone of the event. Carter wore a cardigan, a choice that officially brought the down-home, “folksy” vibe of his campaign into the White House.

Alongside the fireside chat, in the first weeks and months of his presidency Carter deployed a number of gestures meant to reinforce the idea that his election represented a break from the political corruption and crises of the recent past, to bolster his image as someone who was in touch with the concerns of “regular Americans,” and to demonstrate his commitment to the Christian values that helped define his political identity. There were cutbacks of the use of limousines by White House staff; he often appeared in more casual clothes, and eliminated the playing of “Hail to the Chief” at public appearances. The Carter family also hired Mary Fitzpatrick, “a trusty from the Fulton County Jail” who had been wrongly convicted of murder, as a governess for their daughter Amy.

While moves like these were broadly favored by the American people, some Washington insiders criticized Carter for an apparent reliance on symbolic gestures as a way to build political clout. NYT op-ed writer Hedrick Smith wondered if there had been “more symbolism than substance to the early weeks of the Carter Presidency.” The Post’s Edward Walsh noted that Carter’s aides were “almost defensive” when they talked about Carter’s numerous symbolic acts, “fearing that [those acts] will be interpreted as a cynical manipulation of public opinion and sentiment.”

Political symbology that emphasized a spirit of change was in tune with a shared sense that Carter’s inauguration represented the arrival of better days after troubled times. Time’s look at the national mood on the eve of Carter’s inauguration helped saddle the new administration with unrealistic expectations that grew in part out of the folksy vibe that defined Carter’s campaign. Jimmy Carter, Time postulated, represented “the biggest manifestation” of how “the issues and their urgency in a singular way, have been brought closer to earth and home and people” with the political arrival of a man who was “practically unheard of when the Administration now ending first came to power.”

In the funny pages, the “national mood check” was a little more subdued: Joanie tells Rick that, according to Time, Americans were demonstrating “cautious optimism,” and “quiet expectancy” while “turning inward” and feeling a general sense of being “hopeful, sort of” as a new President took office. That said, Trudeau had already begun to spoof the outsized expectations that Carter shouldered.The day before, Mike and Mark offered their analysis of the first ten days of the Carter Administration on Walden’s campus radio station; Mark’s take on Carter’s first week-and-a-half on the job is scathing. While it was “probably too early to talk impeachment,” Carter’s first ten days had been “a national disgrace”: “unemployment has remained high, inflation rages unabated, and crime and poverty still plague our decaying cities … shattering the dreams of millions of Americans who had dared to place their hopes in a man called Carter.” The joke isn’t, of course, that Carter has revealed himself as incompetent within ten days on the job, but that his campaign rhetoric and the resultant media hype created completely unreasonable expectations for a young, hip (in his own way) new President.

Mark’s shattered hopes for the Carter Administration were partially fed by a growing intertwining of the worlds of politics and popular culture, something that has seen much of America’s politicking increasingly come to emphasize style and symbol over substance. As Carter settled into the Oval Office, Rick Redfern had a temporary gig with People, leaving him well-situated to comment on the relationship between pop stars and politicos. Rick’s editor Brenda is blown away by the gossip our intrepid reporter uncovers in his reporting on Carter’s inaugural concert: she’d had “no idea there was so much stroking” going on between Hollywood and D.C. elites backstage. Rick is less impressed: “movie stars and politicians habitually turn into unabashed groupies in each other’s presence. It’s really sort of pathetic.”

The New Spirit Inaugural Concert took place at the Kennedy Center on 19 January 1977. Echoing Time’s unrealistic optimism about Carter as an agent of profound political change, the NYT postulated that the event, which featured older performers like Redd Foxx, John Wayne, and Leonard Bernstein alongside younger stars like Chevy Chase, Dan Aykroyd, Linda Ronstadt and Paul Simon, reflected “a tremendous air of hope … that almost seemed to be running through Washington” as Carter took power. TheTimes described the concert as “truly democratic – with a small ‘d’” : its “emphasis on Black and White (not to mention Hispanic) Americans together,” and its emphasis on “concerns regarding women, equality, old age, peace, and religion” were potentially “the keynote of the incoming government.”

While the concert featured wildly popular celebrities, the “small-‘d’ democratic” aspirations of the Carter Administration were perhaps less visible at a tony Kennedy Center event than they were on 5 March 1977 when Carter took part in “Dial-a-President,” a live phone-in hosted by Walter Cronkite and broadcast nationally on CBS Radio. “Dial-a-President” represented a new development in the history of presidents using technology in new ways to bypass reporters and communicate directly with American citizens, fitting neatly between FDR’s original fireside chats and Donald Trump’s use of Twitter to speak to his supporters in a virtually unmediated fashion.

Reading the transcript of the phone-in, two things stand out. The first is how everyday Americans revealed a sophisticated level of engagement with questions of public policy, ranging from broadly-shared concerns about the economy and taxation to more niche questions about the intricacies of the War Powers Act and horizontal divestiture in the oil industry. The overall tone of the event is also noteworthy. Callers who obviously disagreed deeply with Carter’s approach to a given issue still expressed a strong sense of respect for the man and his office, and most wished him luck moving forward. As compared to our moment, the fundamental civility on display is remarkable. Even given diverging political and policy preferences, there was a shared sense of commitment to making the country work better for its citizens, as opposed to the zero-sum, us-versus-them antagonism that divides people on differing political sides in more contemporary political discourse.

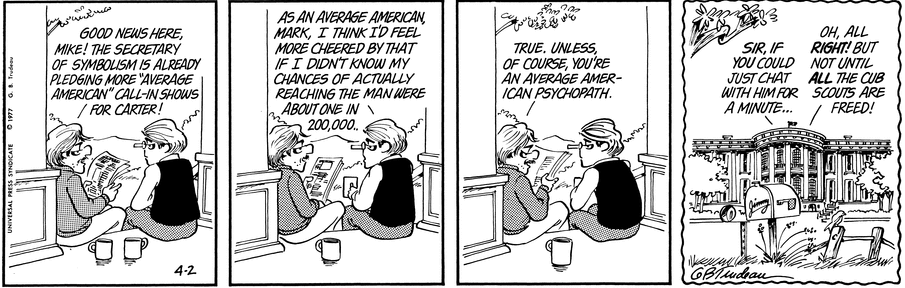

On the comics page, it didn’t quite play out that way. Instead of taking to “average Americans,” Carter is confronted by “average American psychopaths,” including someone holding a troop of Cub Scouts hostage as a ploy to beat the 1-in-200,000 odds of actually getting to talk to the President; another attempt to build stronger connections between the White House and “plain folks” ends when Carter finds himself in an awkward, very personal conversation with an “average American” that may well have marked the first time that the word “hemorrhoids” appeared in a major American comic strip.

(There’s an interesting twist in Trudeau’s coverage of the phone-in, in that it shows him writing a gag about an event that hadn’t even happened when he submitted the strip. On the day Dial-a-President took place, Doonesbury featured an atypical stand-alone daily strip, cutting short a week-long sequence about Henry Kissinger’s new teaching gig at Walden College. The strip, about an agitated caller who rails at Cronkite for insinuating that he was a “nut,” finds Trudeau spoofing an event that, for readers of the morning paper, was only going to happen later that evening.)

For Doonesbury readers, the phone-in and other symbolic gestures like “the cardigan, the limo cuts … and Amy’s ‘trusty’ governess” were the work of a new minor character, White House symbols chief Duane Delacourt, introduced to readers on 21 March 1977.1 Duane’s first appearance echoed a dynamic that had featured in Smith’s aforementioned NYT op-ed (which ran exactly two weeks before Duane’s debut) – a seeming obsession on the part of the White House with Jimmy Carter’s wardrobe choices. Smith noted that on the day of Carter’s fireside chat, some Carter aides “argued that the dignity of his office required him to wear a suit,” while others “advocated the folksiness of a sweater over an open-necked shirt, thinking it would make him appear like a father of the family.” Another “suggested a sweater and tie,” believing it would help the President appear “informal but not gauche.” When we meet Duane he’s in jeans, an open-necked shirt and stocking feet; the folksy vibe is amplified by the fact that he’s working while seated in an easy chair, not behind a desk. He’s talking to someone from the wardrobe department about what Carter should wear for the fireside chat: “I’d like to try a leisure suit on the boss, in … oh, Dacron, polyester, something of this nature.”

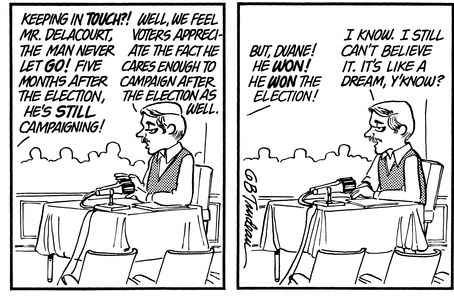

As Delacourt’s skills with political symbology produce one “unequivocal hit” after another, Carter realizes that his work is “too important for a subcabinet operation,” and nominates him “to a new Cabinet post – Secretary of Symbolism.” The subsequent confirmation hearings (…for which Duane chooses a cardigan and slacks…) underline Smith’s observation that “…in Washington, perhaps more than in the country at large,” some voices were dismissing Carter’s numerous symbolic gestures as little more than “a shrewd political strategy.” One Senator chastizes Duane: “Mr. Delacourt, when will you people learn that what this country needs is less public relations and more public service?!” Duane is ultimately narrowly confirmed to the position – marking “a victory for the ‘little guy,’ the ‘man in the street,’ the ‘average Joe,’” – after his testimony ends in an outburst of Congressional frustration, one that echoes Smith’s reporting that there was “still a strong campaign mentality in the White House.” One of Duane’s interlocutors notes that “five months after the election,” Carter was “still campaigning!”

“Well, we feel voters appreciate the fact that he cares enough to campaign after the election.”

“But Duane! He WON! He WON the election!”

Duane’s efforts were central to a couple of great arcs that ran in early 1977. The first of these has to do with Carter’s reputation as the “first rock and roll President.” That’s for next time here. After that, I want to dive into a sequence about a human rights award show that eventually sets the stage for GBT’s coverage of American-Iranian relations at a crucial moment in Middle Eastern history.

Stay tuned.

- Trudeau used the common misspelling “trustee” in the original strip. ↩︎

Reminds me of Justin Trudeau’s first ten days in office. Sunny ways, colourful socks, 50% women in cabinet, and average Canadians “feeling a general sense of being hopeful, sort of”, and wondering if this guy had any actual policies.

LikeLiked by 1 person