Since the emergence of Donald Trump as a political figure, antisemitism has found new public acceptability. From the close relationships Trump and his supporters fostered with alt-right people and outlets including Steve Bannon, Brietbart, and the Daily Caller, all of whom have been linked to antisemitic statements, to his half-hearted condemnation of a white supremacist rally where participants chanted “Jews will not replace us,” to his retweeting of antisemitic imagery, to his own antisemitic statements, it’s clear that antisemitism is a cornerstone of Trumpism. This holds true even as Trump unquestionably supports Israel by recognizing Jerusalem as the Israeli capital and affirming Israeli sovereignty over the occupied Golan Heights. At the same time, criticism of the state of Israel is increasingly being framed as inherently antisemitic. Representative Ilhan Omar has been branded an antisemite for her comments on the power of the pro-Israel lobby in Washington, and America has moved to criminalize protest against the Israeli state, accusing such protests of embracing anti-Jewish discourse.

It was against this background that I read two comics about the relationship between American Jews and the state of Israel: Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less, and Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, a posthumously-published book written by comics pioneer Harvey Pekar and illustrated by J.T. Waldman. Both books are grounded as much in historical and current events in the Middle East as they are in each writer’s personal relationship with those events and their meanings. Glidden’s title foregrounds her key theme: the intensely complex political and moral questions that shape progressive American Jews’ relationship with Israel. Pekar’s title emphasizes the intense sense of disappointment that some progressive American Jews feel towards Israel, a sense that, in Pekar’s case, brings him to ultimately reject the state of Israel as a legitimate expression of Jewish nationhood.

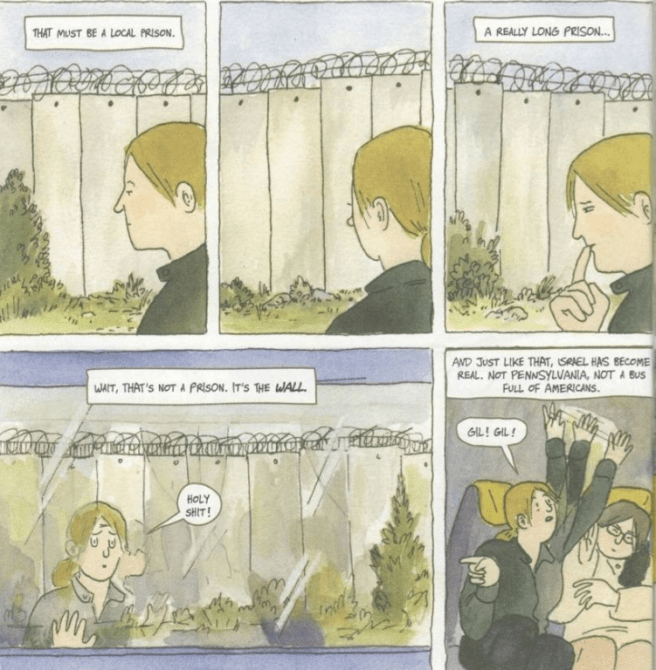

In 2007 Glidden, the author of Rolling Blackouts, an examination of the effects of the Iraq war on the civilian population, spent two weeks in Israel with Birthright, an organization that provides free trips to the country for Jews aged 18-32. Birthright’s stated mission is to “ensure the future of the Jewish people by strengthening Jewish identity, Jewish communities, and connection with Israel.” Critics of the program note its one-sided portrayals of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict and an apparent tendency to emotionally manipulate participants into “equating Jewish identity with Israeli nationalism and Israeli policies.” Birthright may have its propagandistic dimensions, but Glidden’s critical mindset leaves her well-equipped to see through its agenda: leading up to the trip, she immersed herself in studying the history of the region, and she understands that to truly appreciate what is happening in Israel, she needs to witness “the reality on the other side of the Green Line.” Even if she never makes it there, it’s crucial that this idea is in the foreground of her thinking about the trip.

Glidden’s immersion into self-study of Israeli/Palestinian history led to her becoming “alienated” from her friends as she pursued her obsession. Yet when she gets to Israel, she often feels alienated from the object of her study. Birthright offers little opportunity for participants to engage with Israel outside of the framework the tour provides. Glidden rarely encounters Israelis in contexts that are not set up by Birthright. Perhaps more importantly, she encounters few Palestinians or non-Jewish Israelis.

Birthright’s tendency to steer participants away from voices that might challenge the assumptions at the core of its mission inhibits Glidden from doing what she came to do: answer her questions about what Israel should mean to progressive Jews like herself. Glidden knows that “the Palestinians have their own story,” but Birthright is uninterested in letting participants hear it. The people who are perhaps best-equipped to help Glidden work through her internal conflicts over Israel are either absent or they drift across Glidden’s field of vision with her unable to make a connection. At several critical junctions, Glidden finds herself unable to ask the questions that might get her closer to clarity. As a group of Israeli soldiers accompanying her tour leave, she wants to ask them about their experiences: “Do they dread going into the army or do they just accept it?” Are conscripts tasked with some of the more aggressive elements of the occupation of Palestine such as bulldozing homes or capturing militants, or are those jobs left to career soldiers? But the soldiers leave with Glidden’s crucial questions left unasked; the same happens with activists from a peace organization made up of Palestinian and Israeli victims of sectarian political violence.

Yet when Glidden does interrogate the stories that Birthright tells, she cuts through some of the deeply problematic interpretations of Israeli politics, history and society that the organization uses to advance its agenda. When her group spends a day camel-riding with a Bedouin community, she understands that the people leading the trip are “taking us on a tour of their own defeat … [displaying] a bastardized version of their nearly dead culture to the cousins of the people responsible for its death.” Glidden’s depiction of the group’s tour of Masada, the site of a siege during the First Jewish-Roman War that has become a touchstone in Jewish/Israeli nationalist mythology, deconstructs the received historical narrative that frames the episode as an early expression of Jewish national solidarity and shared identity forged in struggle, focusing on how an inaccurate account of the siege has been consciously manipulated to promote a stronger connection between the state of Israel and contemporary Jews.

If there’s any shortcoming in Glidden’s excellent work, it’s that she doesn’t do more to explicitly weave her deep knowledge of the history of Israel and Palestine into her narrative. This is perhaps an unfair criticism, because the story she wants to document is more about her own struggle with that history as she experiences its outcome through the lens that Birthright imposes. The histories that Glidden read to prepare for her Birthright experience form one half of the core of Pekar and Waldman’s Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, a book that balances personal memoir with a deep reading of the history of the Jewish people and the state of Israel. Pekar and Waldman chronicle how the legacy of that history led to Pekar’s ultimate alienation from an ideology that had been a bedrock belief for his family in his youth.

Not the Israel… is set in a single day as Pekar and Waldman ride around Cleveland looking for documentary sources and discussing their project. Pekar alternates between recounting his experiences growing up in a Zionist family as Israel established itself as a nation-state with recounting the longue durée history of the Jewish people. Pekar’s belief that Israeli policies towards the Palestinians represent a betrayal of the potential lessons of the Jews’ history of suffering lead Pekar to abandon Zionism and become a strong critic of Israel. “Jews,” he reasons, “make awkward overlords.”

While the young Harvey Pekar shared his family’s Zionist leanings even as a child he was skeptical about religion: as a student in Hebrew school, he thought it was ridiculous that he was being taught to recite Hebrew texts, but not what the words he was speaking meant. As a young man in the sixties, his associations with Marxists and other leftists led him to question Israel’s actions towards its Arab neighbours, and the the idea of nationalism more generally. “Nationalism and ethnic pride,” he argues, “delay human development, and the misery they cause must be recognized.”

To explain his break from Zionism, Pekar traces the history of the Jewish people from their Biblical origins in the stories of Abraham and Moses, through exile in Babylon, conquest and domination by empires from Alexander to the Romans, the Jews’ expulsion from their homeland the development of the Jewish diaspora, the rise of modern antisemitism in Europe with its uniquely horrific consequences, the emergence of Jewish nationalist sentiment and modern Zionism, the founding of the modern state of Israel, and ending with an overview of the contemporary situation in Israel/Palestine.

Two themes emerge from Pekar’s sweeping recounting of Jewish history. The first is trauma: from their earliest days through the horrors of the twentieth century, the Jewish people have experienced social, political and economic exclusion, expulsion, mass violence, and genocide. The second is the role that the codification of religious thought in the first centuries of the Common Era played in helping to create and maintain a unified sense of Jewish identity that endured through those centuries of trauma. Pekar sees arguments that defend abusive and oppressive Israeli policies as the result of a historical process in which religious thought took the place of secular community building as the foundation for a shared national identity. The words of the Torah and the Talmud revealed to the Jewish people the path that God wanted them to follow and the justification for what they did as they followed it. “How can you change the minds,” he asks, “of people who think they’ve a deal with God that goes back a thousand years?” Pekar had grown up seeing the Zionist project as a chance for the Jews to come home to a place where they would finally break a centuries-long history of exile and oppression; he assumed the Jews’ history of trauma would lead them to imbue their nationalist project with the highest possible moral standards. Instead, the abuse they experienced led them to embrace the idea that, once they had political power, “turnabout on gentiles [was] fair play.”

Yet while Pekar sees the codification of Jewish thought as a crucial dynamic underlying justifications for Israeli policy, the “ism” that he ultimately holds accountable for Israel’s crime isn’t Judaism: it’s colonialism and its basis in perceived racial superiority. It’s impossible to tell the story of the Palestinians without noting their virtual permanent state of colonization, from centuries of being ruled by the Ottoman Turks, followed by the Europeans under the League of Nations mandate system, to now, the Israelis. While Jews in the West eventually managed to at least gain a certain amount of the status associated with whiteness, Muslims and Arabs remained strangers to Europeans and Americans. Pekar notes that “a majority of Jews here in Cleveland wouldn’t complain about Jews being mistreated,” and argues that is because of Muslims’ outsider status as non-whites. The colonialist impulse is, to Pekar, a betrayal of fundamental Jewish values, a betrayal that can be seen in Israeli cooperation with another colonialist state, apartheid South Africa, in the field of nuclear weapons, Israeli arms sales to Latin American right-wing dictatorships such a Pinochet’s Chile, and, ironically, in Israeli cooperation with Iran’s totalitarian theocracy as part of Ronald Reagan’s Iran-Contra scheme. The Jews may be “the most viciously persecuted ethnic group,” Pekar argues, but the policies that the Israeli state has pursued towards the Palestinian people are “not only immoral, but also self-destructive.”

These books deal with the same basic question but come to conclusions that, while not at odds with each other, reveal something of the possible range of positions that progressive Jews may take in regards to Israel’s policy of occupation and settler colonialism. The last panel of Glidden’s book shows her starting to work through what she’d learned during her Birthright trip: “What’s the deal with that place?” she’s asked. After a thoughtful pause, she begins: “Well…” Glidden’s experience in what she calls the “Land of I Don’t Know” has left her with a deeper understanding of the complexities of Jewish identity as seen through both the lens of history and the lens of her brief but intense exposure to a particular vision of what Israel should mean to the Jewish people, but she is still trying to figure out her place. Pekar, on the other hand, sees the history that he recounts to Waldman as leading him to one conclusion: nothing in the region will improve as long as Israel continues to betray the core values that the Jewish people should have taken from that history. At the end of the book, he throws his hands up, seeing Israel’s colonization of Palestinian land as something that demonstrates the fundamental intractability of the problem: “And those religious settlers are claiming that God gave them the land for all time. If that’s the case, then show me the deed.”

Glidden’s drawing style is elegant and understated. Her fine line work and subtle colours add an intimate character to the book, an intimacy that reflects the extent to which the book is a deep exploration of her thoughts and feelings as she engages with a series of difficult experiences and questions. Waldman’s art is more varied and daring. As we travel through centuries of Jewish history, he adapts his visual approach to fit the various eras Pekar is discussing, such as pseudo-tilework images used to represent the Jews’ experiences under Roman occupation or harsh, disjointed and deconstructed imagery that depicts the shock and horror felt by the world in the aftermath of the Holocaust.

Because of growing antisemitism, an American administration that will embolden Israel’s colonialist politics, and the cynical manipulation of accusations of antisemitism used to silence those who criticize those policies, we are in a time when questions surrounding Jewish identity and Israeli policy are only going to take on more weight. Both of these books are important contributions to our understanding of what those questions mean to a community of people who have much to gain or lose on how they are ultimately resolved.

Any criticism of Jews is anti-Semitism.

LikeLike

Duly noted.

LikeLike