On 13 September 2022, Iranian police arrested twenty-two-year-old Masha Amini for not wearing her hijab in the prescribed manner. The police beat her severely; three days later she died from cerebral trauma. In response, under the banner of “Women, Life, Freedom,” Iranians protested Amini’s death, Iran’s systematic oppression of women, and the regime’s very existence. On the streets of Tehran, teenage girls “ripped off their headscarves and chanted ‘Death to the dictator!’”

In focusing on laws restricting women’s dress, those protests echoed a moment from the early days of the mullahs’ rule. On 8 March 1979 – International Women’s Day and mere weeks after the Shah had fallen – Iranian women took to the streets. The march was originally intended to commemorate women who had died during the revolution, but the previous day, the Ayatollah Khomeini had called for Iranian women to “cover themselves to protect their dignity.” Women not wearing the veil were forbidden from entering their workplaces. Thousands of women came out to “protest a return to a custom they regarded as backward and belittling.” The protests lasted nearly a week. Time quoted one Tehrani woman expressing her sense of betrayal at the revolution’s misogynistic turn: “We fought for freedom with the men. None of us knew that freedom would come with chains.” Farzaeh Nouri, a lawyer and activist, denounced mandatory veiling in a speech at Tehran University:

“I’ll never wear a veil … No man — not the Shah, not Khomeini, and not anyone else — will ever make me dress as he pleases. The women of Iran have been unveiled for three generations, and we will fight anyone who bars our way.”

The imposition of the veil became a key theme in Western criticisms of the Iranian revolution. A delegation from the International Committee for Women’s Rights, an organization chaired by Simone de Beauvoir, marched with women in Tehran. Perhaps most famously, the American feminist activist Kate Millett travelled to Tehran to support protests against the imposition of the veil. Milllett’s presence in Iran angered the new regime, and she was deported after a week. Millett also alienated Iranian women activists with her insistence on reading their situation through a universalizing lens of Western, white feminism. One protester told the Times that Millett had “no right to talk for Persian women, …. We have our own tongues, our own demands. We can talk for us. …. “She does not know us. I do not know what she is doing here .”

By the time Iranian women took to the streets, women’s issues and feminist debates had been a regular topic in Doonesbury for several years. A while back, I wrote about how Garry Trudeau’s depictions of women underwent a fundamental shift in the early 70s. When Doonesbury first hit the funny pages, Trudeau, reflecting profoundly misogynistic elements that permeated campus newspaper and underground/comix cartooning, drew numerous strips that either reduced women to the targets of male conquest or ridiculed them for not being attractive enough to pursue. Relatively quickly, however, he began to center the concerns of second-wave feminism in his cartooning, using characters like Nicole and Joanie to sympathetically explore the challenges and changes that women in the 1970s were encountering at home, on campus, and at work.

Given the centrality of women’s issues in Western reactions to the Iranian revolution, Trudeau’s long commitment to injecting feminism into the funny pages, and the number of strips he drew about revolutionary Iran, one might expect to find several instances in which Doonesbury turned a satirical lens on Iran’s oppression of women: in fact, there are only a handful. In this post, I’m going to look at Trudeau’s brief engagement with the politics of women’s clothing in Iran and trace how, beyond satirizing developments in Tehran, Trudeau subtly linked the setbacks faced by Iranian women seeking equality to a broader cultural backlash against feminism’s gains in the 1970s.

The few Doonesbury strips that directly reference Iran’s oppressive dress codes for women lean on ridiculing the regime for its prudishness about Western fashion norms. Three weeks after the protests in Tehran, Walden alum Ali Mahdavi – the comics-page version of US-based anti-Shah student activists like Sharir Rouhani, a Yale grad student who acted as Khomeini’s U.S. spokesman – attended Homecoming. While on campus, he appeared on Mark’s radio show. When Mark asks Mahdavi about the protests, Mahdavi tries to diffuse his critiques of the veil – “a symbol of Islamic sexism” – by pointing out that Khomeini’s statements were “being taken too literally.” The Ayatollah, Mahdavi maintains, simply wants women to be “modest” in public; the objection is to women wearing “skirts and gowns, the garments of prostitutes.”

“I see,” replies Mark. “How about the Annie Hall look?” (Diane Keaton’s fashion sense was recently described by the New York Times as consisting of “high necklines and oddball takes on traditionally male looks — hats and blazers; turtlenecks and button-downs; scarves and ties” – hardly the “garments of prostitutes.”)

“If worn with a veil, fine.”

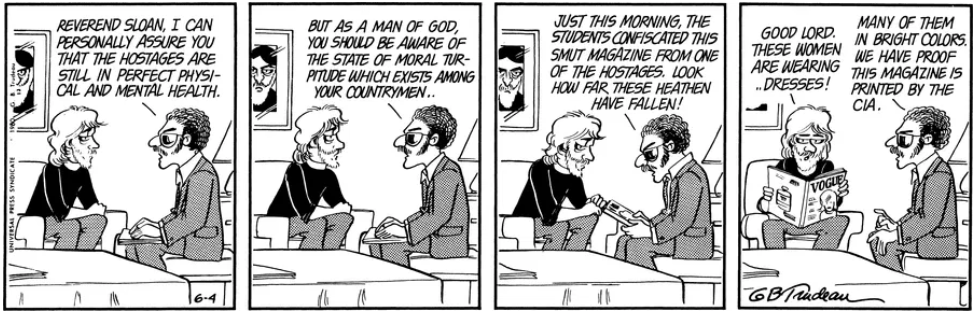

During the Iranian hostage crisis, when radical students seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran and held its staffers for 444 days, Scott Sloan travelled to Tehran to visit the students’ prisoners. Mahdavi again frames Western women’s fashion as, if not the “garments of prostitutes,” sexually objectifying. After assuring Scott that the hostages are in good condition, Mahdavi turns his attention to a bit of contraband the students had confiscated from their hostages: a “smut magazine” that reveals the “state of moral turpitude” pervading American society.

In the final panel, we see Scott looking at the “smut magazine” in question – a copy of Vogue. “Good Lord,” he says. “These women are wearing dresses.”

“Many of them in bright colors,” Mahdavi notes disapprovingly.

These two strips spoof the mullahs’ puritanism and their stated justifications for limiting women’s freedom to choose their own apparel. Khomeini and his supporters saw modern Western secular culture, and not religious tyranny, as the real force oppressing women. By forcing women to make themselves sexually attractive to men, modernity, the mullahs argued, held them back. “Islam,” Khomeini asserted, had “never opposed [women’s] liberty”; rather, it was social reformers like the Shah who had “dragged women to corruption and brought them up as mere dolls.”

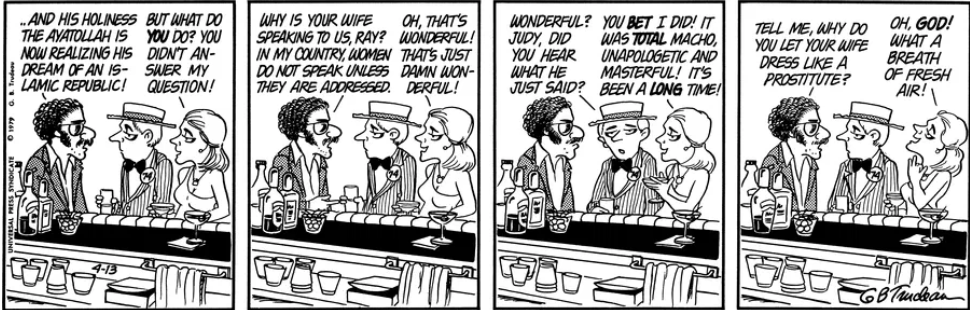

One of Mahdavi’s tirades against Western fashion points to a more complicated dynamic underpinning Western reactions to the imposition of the veil – a new embrace of traditional ideas about relationships between men and women that was unfolding as second-wave feminism was advancing the cause of women’s equality. Back at Homecoming Mahdavi explains to a couple how “the Ayatollah is now realizing his dream of an Islamic republic.” When the woman interrupts him with a question, Mahdavi asks her husband why she was speaking: “In my country,” he explains, “women do not speak unless they are addressed.”

Rather than push back against Mahdavi’s sexist remark, the woman embraces it as a throwback to an earlier era of relationships between men and women. When her husband expresses his shock at Mahdavi’s words, she replies: “It was total macho, unapologetic and masterful. It’s been a long time.”

Mahdavi doubles down on his misogyny by criticizing Western fashion as sexually objectifying, asking the man why he lets his wife “dress like a prostitute,” again centering the link between style and sexual objectification in a critique of Western femininity.

The wife by this point is almost orgasmic in her embrace of Mahdavi’s prudery and sexism: “Oh God!” she exclaims. “What a breath of fresh air.”

The woman speaking with Mahdavi expresses a nostalgia for an earlier style of gendered relationships that was increasingly being consigned to the dustbin of history by second-wave feminism, and, as a result of that, also enjoying a revival in a popular-culture reaction to women’s gains. In 1973, Marabel Morgan wrote The Total Woman, in which she argued that “God ordained man to be the head of the family, its president”; the “total woman” she wrote, “caters to her man’s special quirks, whether it be in salads, sex, or sports. By the end of the 1970s, Morgan’s traditionalist view of gendered relationships pervaded the cultural landscape: the Village People sang about being a “Macho Man”; Faberge released a men’s cologne called simply “Macho.” The feminist film critic Molly Haskell noted that women’s liberation movements “provoked a backlash in commercial film: a redoubling of Godfather-like machismo to beef up man’s eroding virility.”

Much of this anti-feminist discourse was driven by the debate over the Equal Rights Amendment. On March 22, 1979 – two weeks after the imposition of the veil in Iran and three weeks before the “breath of fresh air” strip ran – anti-feminist activist Phylis Schalfly hosted a gala celebrating the passing of the deadline for the Equal Rights Amendment to be ratified by the states and become enshrined in the Constitution. Congress later extended the deadline to no real effect, but for all intents and purposes ERA was dead. Schlafly had played a prominent role mobilizing antifeminist sentiment against ERA; the soiree was her victory lap.

Trudeau by then had already spoofed Schlafly’s retrograde vision of women’s place in American society. In December 1977, Joanie Caucus was called upon to oppose Schlafly in one of the regular debates over ERA that she took part in. Joanie has to face a tough crowd, made up of women who want to hear Schlafly “raise her voice high in defense of family and home” and assume that if Joanie supports ERA, she must be a lesbian. When Joanie argues that American women are “ready for recognition of the very real contributions both spouses make to their marriage,” Schlafly’s supporters greet her with a deafening silence and then start chanting “We want Phyllis!”

Like Schlafly’s supporters, the woman Mahdavi assails at Homecoming represents an antifeminism that clung to idealized traditional gender norms. The “breath of fresh air” strip – drawn just as ERA faltered and as the Ayatollah imposed draconian laws on Iranian women – subtly ties together two important setbacks incurred by women’s equality movements on the international stage in the spring of 1979: the imposition of theocratic misogyny in one country, the failure to codify female equality in another.

Trudeau didn’t dig too deeply into how the mullahs used women’s clothing as a way to reinforce their misogynistic vision for Iranian society, but in at least one strip he framed Iran’s enforcement of the veil as part of something that transcended one nation’s politics and represented a larger reaction against women’s equality that was unfolding in the late 1970s. Though GBT didn’t go farther than that in spoofing Iran’s official misogyny, these strips about the Iranian revolution overlapped with another debate about feminism and women’s clothing – or, more specifically a lack thereof.

A few months before Mahdavi expressed his disgust at the “smut magazine” that the American hostages were reading, his real-life incarnation Sharir Rouhani had noticed the presence of a symbol of another “smut magazine” on display during the Women’s Day protests in Tehran. Appearing on PBS’s Newshour to discuss the protests, Rouhani noted a small detail he had observed, one that reinforced the idea that women protesting the veil embodied Western secularism’s objectification of women: some of the protestors were “wearing Playboy shirts.”

Rouhani’s mention of the presence of Playboy’s signature rabbit-head logo on the streets of Tehran overlapped with a Doonesbury storyline about the magazine that unfolded soon after his comics-page stand-in attacked a Walden alumna for dressing “like a prostitute.” Weeks after the protests in Tehran, Trudeau turned his attention to an edition of a “smut magazine” that also drew sharp criticism – not from Iran’s religious fundamentalists, but from American feminists: a Playboy picture spread featuring the “Women of the Ivy League.”

Next time out: Playboy comes to Walden.

(A note to readers: recently, GoComics put their archives behind a paywall, and the official Doonesbury website’s archives don’t go back far enough for me to link to most strips. If there’s a strip you really need to see, drop a line, and I’ll hook you up.)

The link to the radio show doesn’t work for me (gives a 404 page), but shouldn’t that be “Rouhani” (in the real world) rather than “Mahdavi” (in the comic) who noted the Playboy shirts? Sorry to be nitpicking for a second article in a row!

LikeLike

Rob!

You’re absolutely right about the Mahdavi/Rouhani screw-up. Fixed.

I’ll see what’s happening with the NewsHour link tomorrow.

Thanks so much for reading, and for the editing tips!

LikeLike

You’re welcome, and I don’t know if you changed anything but the link is working now.

LikeLike