In November 1978, as protests against his regime escalated, the Shah of Iran instituted military rule and clamped down violently on street demonstrations. In an interview with The MacNeil/Lehrer Report, Shahriar Rouhani, an Iranian anti-Shah activist and a doctoral candidate in physics at Yale, described the situation in Iran as “a mere calm before the storm.” “The Iranian people,” Rouhani told Robert MacNeil, had “not stopped the movement by any means.”

As Rouhani had predicted, protests against the Shah escalated, and were met with increasing violence. In January 1979, the Shah appointed Shahpur Bakhtiar as Prime Minister before fleeing the country, never to return. On 31 January, the exiled dissident fundamentalist cleric Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini took power. Iran fell into political chaos as the new regime exacted revenge on the old one, purged itself of its secular/leftist factions, and then set its sights on the Iranian people with a view to creating a society built on a narrow, extremist reading of Islamic doctrine.

Any hopes that liberation from the Shah would bring the Iranian people the benefits of liberal democracy were quickly dashed as the Ayatollahs imposed their fundamentalist visions on Iranian society. On 26 February 1979, the New York Times reported from Iran that a burglar and two men caught drinking had been publicly flogged, the robber getting twenty-five lashes to the drinkers’ eighty. A week later, the Times further detailed Iran’s slide into religious tyranny, reporting that as Khomeini urged Iran’s courts to reject Western juridical principles such as the right to appeal, officials from the former regime, including an alleged SAVAK “torture expert,”(SAVAK was the Shah’s secret police force) had been summarily executed. On 13 March, the paper reported that Iran had executed another eleven people associated with the Shah. While some of them had allegedly committed “murder, torture, and sexual offenses” in the Shah’s name – and there’s no reason to doubt the truth of those charges – two of them, Mahmoud Jaffarian, the former chief of Iran’s state press agency, and Parviz Nikkhwah, a former news editor of Iran’s national broadcaster, were killed “simply for having espoused the positions of the deposed Government of Shah Mohammed Riza Pahlevi.” Later that week, the Times described how trials involving former government officials typically “lasted only a few hours,” and, with one exception, had all “resulted in immediate execution by firing squad.”

Around the time that the Shah fled Tehran, Shahriar Rouhani’s name reappeared in the headlines following a takeover of the Iranian embassy in DC by US-based anti-Shah activists, many of whom, like Rouhani, studied at US universities. Iran’s official representatives were kicked out and Rouhani became the de facto top Iranian diplomat in the United States. The Washington Post described Rouhani as “outgoing, cordial, [and] handsome,” and noted that he “[spoke] in measured terms about the volatile Iranian situation and the fruits of revolution.” A subsequent article detailing the situation at the embassy revealed a darker undertone to events unfolding there. The Post described how an “internal committee,” charged with “[purging] the chaff from the wheat among the 55,000 Iranian citizens in the United States” went about its business. “Three stocky, bearded students” who sat with their feet on the table grilled a career diplomat about “the reactionary or revolutionary qualities of his former colleagues.” When his interview concluded, the “shaken victim” told the Post that the session was “worse … than the loyalty tests [he’d] had from SAVAK.”

Rouhani told the Post that during his time on US campuses he’d balanced “being a good student” with a “full-time political role” as an anti-Shah activist, and credited “the cross-disciplinary approach of the American schools” for shaping his worldview. In the 1970s, as part of a wide-ranging modernization program, the Shah began sending thousands of young Iranians to Western universities. Those students didn’t just learn about engineering or medicine: they also absorbed political ideas and visions for Iran’s political future that were incompatible with how the Shah maintained an iron grip on power. Students like Rouhani played key roles in resistance to the Shah’s brutal rule. Working through groups like the Iranian Student Association, which embraced a more secular leftist position, and the Organization of Iranian Muslim Students, a conservative, Islamist-oriented movement, Iranians studying in the US exposed the Shah’s atrocities and criticized American support for the Pahlavi regime. Iran’s turn towards Islamic theocracy reflected the political visions of those latter, fundamentalist-leaning student-activists, but, perhaps reflecting the hope that Iran was transitioning to a more democratic political climate, some official voices focused on how the liberal values at the heart of American campus culture had shaped Iran’s young revolutionaries. After meeting Rouhani, Jimmy Carter’s UN ambassador Andrew Young observed that it was impossible to “send 25,000 to 50,000 Iranians a year to this country … and then let them go back home, without getting some kind of social upheaval.” However, Young believed that any “social upheaval” Iran might experience would be tempered by the values that young Iranians had been exposed to during their American stays. Young saw Western-educated Muslims as a modernizing force in the Muslim world and remained confident (until rather late in the game) that it would be “impossible” for Iran to become “a fundamentalist Islamic state” because “too much Western idealism has infiltrated that movement.”

Young went on to speculate that Ayatollah Khomeini would someday be recognized as “a saint.”

Garry Trudeau did not share Young’s misguided optimism about the democratic potential of the Iranian revolution. His first strips about revolutionary Iran focused on how Khomeini’s regime betrayed any commitment to the core liberal values underpinning US academic culture, a culture that was formative to Trudeau and his work. Doonesbury began life in the Yale Daily News as Bull Tales, and most of Doonesbury’s storylines from the 1970s unfolded in and around classrooms, student housing, football practices, or the Dean’s office. The overlap between Doonesbury’s focus on campus life and the centrality of student-activists to developments in Iran gave Trudeau ample opportunity to expand his longtime reliance on campus humor to satirize Iran’s descent into theocratic madness.

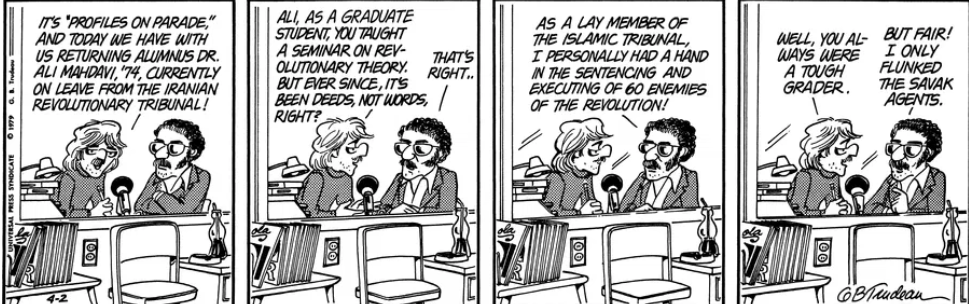

On 2 April 1979 Ali Mahdavi, Shaharir Rouhani’s comics-page incarnation, made his Doonesbury debut as a guest on Mark’s campus radio show. Mahdavi was a former Walden graduate student (class of ‘74) who was “currently on leave from the Iranian revolutionary tribunal” to attend Homecoming. Mahdavi’s descriptions of his work for the revolutionary tribunal echoes those reports from the Times detailing the violence committed by Khomeini’s government. Mahdavi makes no attempt to hide the brutality of the regime he helped bring to power. He answers Mark’s question about the transition from “[teaching] a seminar on revolutionary theory” to a radicalism focused on “deeds, not words” by boasting that, “as a lay member of the Islamic tribunal,” he’d “had a hand in the sentencing and executing of 60 enemies of the revolution.” When asked about the extent of de-Westernization efforts in the new Iran, Mahdavi replies that “Western influences and customs [would] simply not be tolerated” and reveals that “offenders have already been put to death.” Mahdavi himself had “personally condemned two joggers.” Later, at a homecoming reception, a fellow alum asks Mahdavi about the punishments meted out to criminals in Iran: “C’mon, you don’t really cut off their hands, do ya?”

Mahdavi’s reply is blunt: “Let’s just say we go by the book.”

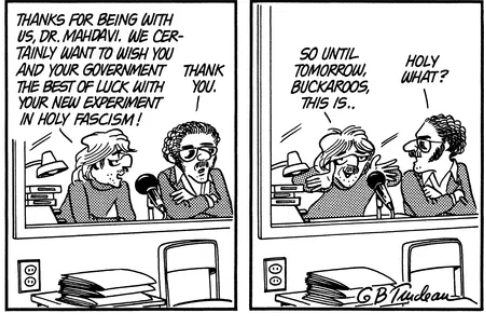

What Mahdavi called “going by the book” Trudeau rightly saw as a complete rejection of modern liberal values. Mahdavi makes it clear that there was little room for Enlightenment ideas about the freedom and dignity of the individual in the regime’s vision for Iran. A recent NYT article had framed the Iranian revolution as a project to create a government “of the type seen during the 1ten years of the rule of the Prophet Mohammed and the five years under his son‐in‐law, Ali, the first Shiite Imam”; something that happened 1,300 years ago.” Evoking this expressed desire to undo more than a millennium’s worth of advances, Marks asks Mahdavi about criticisms that “the Ayatollah’s Islamic republic [was], in effect, returning Iran to the 14th century. Mahdavi offers a potential compromise position that reveals the limited space for modern thought in the revolution’s self-conception. “Some of us,” he concedes, “are trying to get it moved up to the age of Voltaire.” Mark doesn’t buy it for a second: signing off, he thanks Mahdavi for appearing on his show, and wishes his country “the best of luck in [its] experiment with holy fascism.”

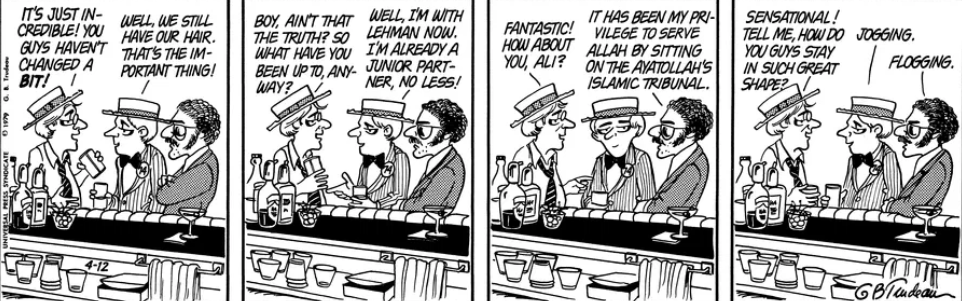

As dark as Mahdavi’s descriptions of conditions in Iran might be, and as pessimistic as Trudeau was about Iran’s future, GBT lightens the mood by framing the revolution’s spokesman as just another guy attending his class reunion, juxtaposing floggings, sham trials and executions against the mundane experience of middle-aged people reminiscing about their time on campus and exchanging updates about former classmates.

Well before the Shah fled his country, Trudeau used the realities of student life to spoof Iran’s revolutionary politics. When the Shah’s wife Farrah attended a dinner in her honor in New York City a year before the collapse of her husband’s government, Trudeau drew a series of strips about the demonstrations her appearance engendered. Covering the event, Roland Hedley interviewed two protestors, both students in the foreign affairs seminar that the comics-page version of Henry Kissinger had recently started teaching at Georgetown (…away from the funny pages, Kissinger was a longtime Shah supporter and actually attended the dinner in question). Kissinger’s students wear simple paper masks, emulating Iranian student protestors who needed to protect themselves and their families from violent retribution at the hands of SAVAK. Roland asks the pair if their masks are necessary: “Surely you’re not protecting relatives or loved ones in Iran?”

“No,” replies one. “But we’ve got mid-terms coming up.”

Trudeau’s subsequent cartooning about Iran built on that juxtaposition of political terror and the daily goings-on of campus life. Mark’s wide-eyed horror at Mahdavi’s admission that the revolution had put people to death to eliminate “Western influences and customs” is balanced against his ribbing Mahdavi about how his hardline positions echoed his approach in the classroom: Mahdavi had “always [been] a tough grader.” When Mahdavi meets up with old friends at his class reunion, the banal conversations that typically unfold between people who haven’t seen each other for years take on a bizarre, macabre tone. One alum asks his pals how they’ve managed to stay in shape: one replies “Jogging.” Mahdavi’s answer: “Flogging.” Another former classmate asks Mahdavi about “that other Iranian kid “ they’d played soccer with.

“Kaleb Zahedi?”

“Right. Whatever happened to him?”

“He went to work for the Shah. I had to have him arrested for high crimes against the state.”

Students continued to play key roles in Iranian radical politics after Khomeini took power. Following the initial rush of the Shah’s overthrow, Iranian students seized the US embassy in Tehran and held fifty-two (or, as we’ll see in a later installment, fifty-three if you count Duke) diplomatic staffers hostage for 444 days. That said, Shaharir Rouhani, the rebellious physics student who had helped seize Iran’s U.S. diplomatic mission in the name of the Ayatollah, ultimately broke with the regime, disillusioned by how “thousands of Khomeini’s young opponents [had been] sentenced to death.” In 1997 he publicly supported the presidential candidacy of Mohammed Khatami, who ran as a moderate reformer. Time noted that Khatami supporters included women “chafing at dress codes” that had been imposed on them in the wake of the Islamic revolution. Next time out, we’ll look at a few Doonesbury strips focused on how the Ayatollahs’ regime targeted women’s wardrobes, and see how Trudeau’s commentary on the clothing restrictions imposed on Iranian women overlapped with a moment that reflected very different ideas about how women could be represented in the public sphere, when a Playboy photographer showed up at Walden College.

Was Kissinger’s class at Walden in the Doonesbury world? I thought it was at Georgetown (as it was in the real world), where Honey later joined the class (and became JJ’s roommate). I haven’t yet shelled out for access to the GoComics archive, so I can’t check for myself.

LikeLike

Indeed it was. Always as an off-panel voice. Honey was in the seminar, too.

Once l finish the Iran strips, l’m starting a deep-dive on the Kissinger stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, wait, you’re right. Honey went to Georgetown.

I’ll have to fix it.

LikeLike

Hello,

I just want to say that I love this blog.

However, I have a question. Would you ever consider using the Washington Post archive instead of the (subscription blocked) GoComics?

Keep up the good work,

James

LikeLike

James,

Thanks for the kind words, and thanks for reading.

If the WAPO archives are working again (….they have been wonky in the past) l’ll definitely consider switching to those.

Peace.

LikeLike