Welcome to the final instalment of my look into how Garry Trudeau has covered Donald Trump since first introducing him to Doonesbury in 1987. In this concluding post, I want to look at how Trump’s dominance of the political moment presents new challenges to satirists, and how those challenges have shaped Trudeau’s work in the decade since Trump became the central figure in American politics.

In my last post, I mentioned a February 2025 strip in which Trudeau argued that the citation of his work in a prominent defamation case protected him from potential retaliatory presidential libel suits. The strip features Mark giving a pretty dry reading of relevant defamation law, the punchline coming with Mike’s interjection: “Wait. Doesn’t satire have to be funny?”

As Mike reminded Mark that satire’s ultimate job is to get a laugh out of the reader, he might well have asked a follow-up question: “And if satire is supposed to be funny, does simply repeating someone’s words verbatim count?” These days, a lot of satire isn’t particularily funny because satirists lean heavily on using Trump’s own words as the punchline.

Doonesbury is no exception to the trend of satirically using Trump’s own words against him. Trudeau did it before Trump had even clinched the 2016 Republican nomination. In 2015, during the GOP debates in which Trump established himself as a viable presidential candidate (the Huffington Post had relegated coverage of Trump’s campaign to its Entertainment section), Trudeau mocked Trump’s tendency to talk over his debate opponents – a habit that eventually led to candidates’ mics being muted during later presidential debates. We see an oversized drawing of Trump at the debate, his combover exposing his bald head. Trump’s opponents (Remember Scott Walker? I don’t.) are obscured by his speech bubbles, which consist entirely of direct quotes of his public statements: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending the best! They’re rapists!”; “It doesn’t matter what the media write as long as you’ve got a young and beautiful piece of ass!”; “If I were starting off today, I’d love to be a well-educated Black!”

A strip that ran in May 2017 adds a twist, putting a verbatim Trump statement from a recent press conference into the mouth of Trump as a middle-schooler. “Li’l Donnie Trump,” asked by his teacher about the threat that Russia poses to Europe, replies with a stream of vapid BS that makes it clear he has no idea what he’s talking about:

Well I want to just start by saying hopefully they are going to have to fear nothing ultimately. Right now there is a fear, and the problems, there is certainly problems. But ultimately I hope that there won’t be a fear, and there won’t be problems, and the world can get along, that would be the ideal situation. It’s crazy, what’s going on, whether it’s the Middle East or… you look at no matter where, the Ukraine, you look at… whatever you look at, it’s got problems, so many problems. And ultimately I believe that we are going to get rid of most of those problems, and there won’t be fear of anybody. That’s the way it should be.

These were Trump’s comments at a press conference he’d held with NATO’s Secretary-General. Trudeau doubles down on the fact that he’s using Trump’s own words to mock him by supplying a handy footnote, allowing interested readers to check out his sources.

This strip hits harder than others that lean on Trump quotes to make their point. Having Trump’s words voiced by a high-schooler reveals how, even in old age, his basic character remains that of a lazy, entitled rich kid whose privilege allows him to coast through life, and that he’s no more ready for the Presidency than he was for civics class.

To some extent, the prominent place given to Trump’s own words by satirists reflects what second-rate humorists are often guilty of: reaching for the low-hanging fruit. In 2018, Washington Post books columnist Ron Charles called satirists to tasks for producing “lazy,” “bland” humor that failed to rise to the challenges represented by Trump’s presidency. That said, using Trump’s own words to take him down a notch can be less a sign of laziness than a reflection of how Trump is so uniquely terrible that satirizing him is nearly impossible. Signalling the extent to which the news has simply become too bizarre to mock, a recent Atlantic article detailing some of the weirder developments of Trump’s second term is titled “Trump’s Tactical Burger Unit Is Beyond Parody.” Satire depends on exaggeration, but little about Trump – his criminality, his instability, his lack of empathy, his contempt for his fellow citizens – can be meaningfully exaggerated. Trump is a walking self-parody, leaving little room for the satirist to develop an inflated depiction that reveals his shortcomings.

To a certain extent, there’s really nothing new at play here. During the George W. Bush years, Hunter Thompson outlined the frustration that came with trying to make meaning out of times so bizarre that they ranged beyond the language typically employed by social critics:

We are living in dangerously weird times now. Smart people just shrug and admit they’re dazed and confused. The only ones left with any confidence at all are the New Dumb. It is the beginning of the end of our world as we knew it. Doom is the operative ethic.

Going back further, in 1961 Philip Roth described the politics of the moment as an “embarrassment to one’s own meagre imagination.” Politics was “continually outdoing our talents” as “the culture [tossed] up figures almost daily that are the envy of any novelist.” Shortly before his death, Roth was asked if Trump “[outstripped] the author’s imagination” in new ways. For Roth, it wasn’t “as a character, a human type” that Trump defied imagination; what defied imagination is that a “callow and callous killer capitalist” had become President.

There is, however, a new dynamic at play: Trump is not only resistant to satire because of his unique awfulness but because those impossible-to-exaggerate elements of his being are precisely what inspire much of his supporters’ adulation in the first place. As the media scholar Alex Symons notes, Trump’s repulsiveness and total disdain for norms give MAGA-Americans exactly what they’re looking for: a near-complete rejection of the established order. If satire is meant to overturn conventions and deliver – even if only for as long as it takes to read a comic strip – “liberation from all social propriety” and “political structures,” what is the parodist to do with a subject whose entire being is about eschewing social propriety (“If Ivanka weren’t my daughter, perhaps I’d be dating her”) and trampling over established political structures (by hiring a ketamine-addicted internet troll to dismantle the federal bureaucracy)?

Trudeau has embraced the challenge that Trump presents to established modes of satire. In the foreword to Yuge, he acknowledges that while Trump may appear to be “beyond satire,” the pros “know he is satire, pure and uncut, free for all of us to use and enjoy, and for that we are not ungrateful.” Trudeau concludes: “For our country though, we can only weep.”

That last bit’s not quite true. Garry Trudeau and some of his contemporaries are doing more than weeping for their country. They’re using satire to actively defend its institutions from the existential threat MAGA poses.

Even as he was appalled by a Trump presidency, Roth remained confident that, even with someone so “destitute of all decency” in the White House, writers would “continue robustly to exploit the enormous American freedom that exists” to speak truth to power. Roth trusted that dissident voices would continue to hold powerful people to account, but media scholar Sophia McLennen sees new political possibilities in Trump’s inherent ability to defy satire. Trump’s embrace of his over-the-top repulsiveness undermines the ability of traditional parodists to take down powerful figures, but it also helps create the conditions for “a reinvention of satire’s primary mode of representational defiance.” Trump’s attacks on core government agencies and key international partnerships forced satirists to reimagine their social role, and defend the Establishment that they historically tore down.

Trudeau’s Trump-era work reveals his understanding of the gravity of the situation, and his desire to use his voice to stand up for the institutions that underpin American democracy. GBT outlined the damage MAGA could inflict on the safety nets protecting America’s most vulnerable citizens. An August 2017 strip sees Mark talking to Alice and Elmont about Trump’s efforts to dismantle Obamacare. The unhoused couple think Trump’s alternate plan will be a “disaster” for them: Elmont, after all, has a “pre-existing addiction” to insurance. Trudeau also warned his readers about the incredible scope of Trump’s wrath. In August 2018 Jeff, in his Red Rascal incarnation, receives a hit list made up of “America’s enemies … personally selected by the President.” Trump charges the Red Rascal with the elimination of political figures ranging from Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, and Jeff Sessions through Barack Obama, Elizabeth Warren, and Ruth Bader Ginsberg; institutions like the federal courts, the Justice Department, and the Veterans’ Administration; and international bodies including NATO, NAFTA, and the G-7.

As the Red Rascal got his marching orders, Trudeau advocated for traditional political institutions and actors as bulwarks against Trump’s threats. In 2018, Melissa – an Afghanistan veteran whose story we followed as she was raped by her commanding officer and then addressed the resulting PTSD – ran for Congress. Her campaign and tenure as a House Representative underline’s Trudeau’s faith that, even with the chaos injected by the Trump presidency, the system still could produce leaders whose commitment to conventional politics would protect the values and institutions upon which democratic governance relies.

Melissa’s campaign was inspired by her desire to be a voice for vets, “to make sure our country does right by them.” But she’s no one-issue candidate: outlining her platform to volunteers, Melissa lists some of the critical programs threatened by Trump: “…cutting food stamps and Medicaid, tripling assisted housing rents, tearing apart refugee families, eliminating Meals-on-Wheels and heating fuel assistance …” Addressing a rally, she frames her bid as an attempt to bolster “a cowardly Congress” against “an authoritarian sociopath.”

Melissa isn’t the only woman in the Doonesbury cast whom Trudeau harnessed to defend the normal functioning of government from Trumpism. In March 2019, we caught up with Honey, now a development minister in the Chinese government. A Trump aide calls Honey seeking advice on infrastructure development. Honey outlines China’s Belt and Road Initiative, “an integrated system of economic development, with land and maritime trade corridors linking China to 68 partner countries.” She wraps up her conversation with her U.S. counterpart with an observation that reveals the extent to which Trump was failing to meet new global political and economic challenges: “We’re spending $1 trillion to connect the world, while you’re trying to spend $5.6 billion to keep the world out.”

The $5.6 billion Honey refers to is the sum bookmarked earlier that year to fund Trump’s border wall – literally “keeping the world out.”

It shouldn’t fall on comic-strip characters to defend government institutions. They certainly shouldn’t be called upon to protect public health against uncaring and incompetent leaders. There’s a history of comics characters being deployed to promote public health: in 1968 Charles Schulz used a week’s worth of Peanuts dailies to promote the measles vaccine for children. With the arrival of COVID, Trump’s mostly feckless response to the crisis, and the embrace of whackaloon COVID conspiracy theories by his followers, Trudeau drew several strips that advocated for the essential institutions that Trumpism threatened.

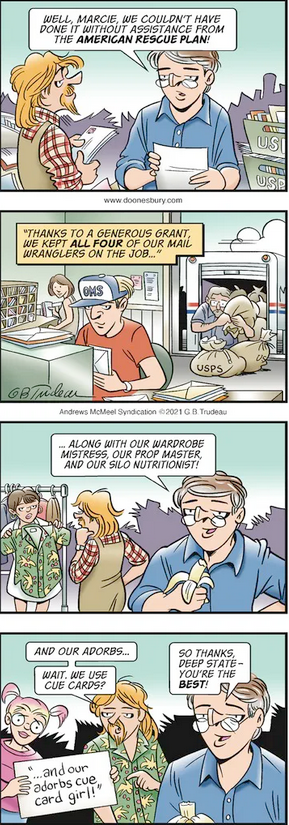

As COVID raged, Trudeau attacked MAGA’s disregard for expertise, advocating for crucial institutions like Anthony Fauci’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and programs like the American Rescue Plan. In one strip, Roland interviews someone at a “fire Fauci” rally who poses the essential question driving MAGA’s response to the crisis: “Who you gonna believe, the President or a bunch of swamp scientists?” In another strip, Zonker and Mike praise the American Rescue Plan for supporting the Doonesbury mailbag crew during the pandemic, allowing them to keep their mail-wranglers, stagehands, and a totally “adorbs cue-card girl” on the payroll.

Trudeau could hardly have been more explicit in his argument that it was the very government institutions threatened by Trumpism that did the vital work of keeping American society functioning during a prolonged crisis. The strip ends with Mike expressing his gratitude to those necessary institutions:

“Thanks, Deep State – you’re the best!”

In a recent On the Media segment, New Yorker staff writer Andrew Marantz observed that attempts to criticize the Trump Administration for its unprecedented attacks on Establishment politics carry a particular risk – reinforcing a status quo that failed to meet core “small-d” democratic values. And while there’s no doubt I’d rather live under a Biden or Obama presidency, or even a George W. Bush one for that matter, than under Trump, to accept many of their policies as “normal democratic politics” sets the bar awfully low. Marantz asserts that Americans can’t “glorify the status quo ante and say, if we could just get back to that, everything would be perfect.” He reminds us that the Patriot Act and “droning American civilians,” a key element of Obama’s approach to the War on Terror, undermined American democracy. So to, he could have added, did Biden’s largely unwavering support for Bibi Netenyahu, even as it became clear that Israel was perpetrating a genocide in Gaza.

In the wake of the January 6 insurrection, GBT’s cartooning in defense of politics-as-normal found him not merely providing satirical observation, but promoting active cooperation with law enforcement in the service of protecting democracy, even as those institutions have a long history of actively stifling democratic movements.

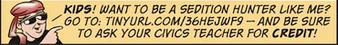

In the wake of the attack on the Capitol, “Sedition Hunters” across America combed footage from the riot, social media posts, and other sources to identify and report insurgents to an FBI tipline. On 10 March 2024, Zipper dropped in on Jeff, who was busy looking through January 6 footage, gleefully nailing down an ID for “#OrangeHatGuy.” The final panel features a note from the Red Rascal: “Kids! Want to be a Sedition Hunter like me?” There’s a now-dead URL for the tipline, and a friendly reminder to “ask your civics teacher for credit!”

Things get messy here.

The January 6 insurgents should have been prosecuted for attempting to overthrow the government – a violent threat to democratic rule demands no less. In the internet age, crowd-sourcing huge amounts of data to find dangerous actors makes strategic sense. Trump’s pardon of the January 6 insurgents remains among the most appalling acts of his second term.

It’s also true that the FBI, like virtually every element of the American justice system, is no friend to marginalized groups or progressive activists. From Indigenous and African-American resistance movements through anti-war and environmental activist groups, people working to create a fairer and more democratic country have been systematically targeted, often violently, by the same institutions charged with investigating and prosecuting the MAGA insurgents.

On the second anniversary of the Kent State massacre, Garry Trudeau ran a strip in which, with one sentence – “Have a nice day, John Mitchell” – he savaged the entirety of the federal justice system for its complicity in the deaths of innocent campus activists (Mitchell was the Attorney General and the country’s top law enforcement officer; he refused to empanel a grand jury to investigate the murders). Fifty-two years later, he encouraged his readers to help the system do what it failed to do when Mitchell refused to pursue justice for Kent State – hold accountable people who violated basic democratic principles.

Trudeau is fond of Finley Dunne’s adage that satire should “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” What it means to “comfort the afflicted” has changed: it’s no longer sufficient for those with a public voice to help people through the madness by providing them with a chuckle. As far as daily comic strips go, Doonesbury represents a radical voice. Trudeau has done as much as any other newspaper cartoonist to push against the boundaries of who gets to enjoy American freedoms; he’s also taken well-meaning liberalism and campus radicalism to task for their clumsy attempts to address structural inequality and injustice. Doonesbury remains vital after all these years because Garry Trudeau has found ways to remain in tune with the times and adjust his work to speak to its particular moment. He remains a radical voice within the limits imposed by his chosen medium. What’s changed over more than a half-century is that now, in this time of monsters, standing up for a deeply problematic “normal” has become a radical act.