In our last look at Doonesbury during the Carter years, we saw how Jimmy Carter’s fondness for political symbolism – initiatives like a “human rights award banquet” meant to bolster a new, rights-driven approach to foreign policy – played into Garry Trudeau’s takedown of the American political and cultural Establishment’s hypocritical support of the Shah of Iran’s brutal regime. After a February 1978 sequence that focused on how figures as diverse as Henry Kissinger, Ed Koch, Shirley MacLaine and Barbara Walters supported the Shah’s torture state, Iran fell off of Trudeau’s radar for a year, only to reemerge, as it did in real life, as an unpleasant reminder that America’s foreign entanglements sometimes had disruptive effects on domestic politics.

Jimmy Carter’s 1979 State of the Union address was a call to build a “new foundation” for those who would be born that year and “come of age in the 21st century.” (…in other words: Millennials, this is for you!) During an interview a few months before the State of the Union, Bill Moyers had stumped Carter when he’d asked him to clearly define the “single theme” of his presidency. In fact, many of Carter’s aides felt that “there was no clearly identified theme to the Administration,” and tried to articulate a set of guiding principles. The idea of a “New Foundation” – reminiscent of FDR’s “New Deal” or JFK’s “New Frontier” – was loosely workshopped in the wake of the interview, but the metaphor didn’t gain traction until later, when Carter expressed frustration with a first draft of his State of the Union speech. He wanted something that would speak to “the difficult nature of the problems we face now, of the difficulty in developing long‐term solutions.” The concept of a “new foundation” was resurrected: aides felt it fit Carter’s needs “like a glove,” and it became the central theme of Carter’s address.

Coming after years of economic stagnation, unemployment, and inflation, the “New Foundation” speech focused on economic growth and stability. Carter proposed free-market-first policies that presaged the gutting of the state that began in earnest under the Reagan Administration, including budget cuts meant to address a spiralling national debt (even as his proposed 1979 budget ran 8% higher than the previous year, and ran a deficit almost a third higher than two years previous) and corporate deregulation intended to promote the private sector. Carter envisioned a leaner, more fiscally-responsible state, calling for a wholesale reevaluation of social spending and a process to ensure that “when government programs have outlived their value, they will automatically be terminated.”

While Carter’s “New Foundation” speech presaged a turn to the right that would define American politics for decades to come, it had a massive blind spot when it came to an ongoing crisis that would, as much as economic questions, contribute to Carter’s 1980 reelection defeat: the ongoing Iranian revolution, which, in November 1979, led to a takeover of the US embassy in Tehran and a hostage crisis that lasted more than a year. In response to Carter’s address, Trudeau drew an arc that hinted at the way in which the unfolding disaster in Iran would have catastrophic consequences for Carter’s presidency and for the United States more broadly. That said, the sequence is worth digging into not only because it helped set up much of what was to come both on the front page and in the funny pages, but also because they point to an important development in GBT’s evolution as a cartoonist.

Trudeau’s reaction to the speech envisioned a construction crew charged with building the structures that would support Carter’s vision for the next century and encountering numerous problems that leave the project a shambles. The strips were in keeping with a number of contemporary critiques of Carter’s vision that deployed metaphors about shoddy building practices. The New York Times noted that reactions from Congress and the Federal Reserve Board “showed how shaky political foundations built on economic assumptions can be.” GOP Representative Barber B. Conable, who sat on both the Budget Committee and the Ways and Means Committee, described Carter’s plans as being “built on somewhat shifting sands.” A Jeff MacNelly cartoon shows Carter working on a construction site. A sprawling edifice, with sections labeled “New Deal,” “Fair Deal,” “New Frontier” and “Great Society” – the key Democratic Party programmes of the preceding half-century – is being built on top of a modest house: the address on the mailbox reads “1776.”

Trudeau’s week-long reaction to the speech opened on 19 February 1979 with an aide telling White House Chief of Staff Hamilton Jordan that contractors had arrived to “start work on the ‘New Foundation.’” From the outset, an air of pessimism hangs over the project: when Jordan asks about the contractors’ “experience in shaping America’s future,” they note that they had “once put up a structure of peace for Henry Kissinger.” “Great,” Jordan responds in a pessimistic tone. More than a random dig at everyone’s favorite war criminal, the strip recalls Kissinger’s 1973 Nobel acceptance speech, which had also deployed a construction-based metaphor, this time as a way to frame proposals that in reality stood in marked contrast to Kissinger’s actual approach to foreign relations. (“America’s goal is the building of a structure of peace, a peace in which all nations have a stake and therefore to which all nations have a commitment.”) As it turns out, the construction crew would have about as much success with the “New Foundation” as they did with Kissinger’s “structure of peace.”

Much of the sequence focuses on the economic challenges facing the Carter White House and the political obstacles that stood in the way of building the New Foundation. Carter’s pledges to cut government spending and open up the market pose particular challenges: as the workers try to “put a ceiling on spending,” the structure collapses, the contractors unable to “find the right framework” to “reinforce the private sector.” When Carter calls Jordan to ask how things are going, the news isn’t great. Jordan reports that “they can’t find any support” for the project: “Conservatives are irate over the cost overruns, and liberals are miffed by the missing planks … even the moderates are saying we bungled the specifications.”

As they wrestle with finding sufficient domestic footing for the New Foundation, the builders have to account for the crucial – if not existential– geopolitical dynamics that underpin Carter’s entire vision for the project. Jimmy Carter won a Nobel Peace Prize for his post-presidential humanitarian work, but as President, he was a Cold Warrior through-and-through. Any commitment he made to a foreign policy based on human rights was balanced against the larger priority of countering the Soviet Union with overwhelming nuclear force. There’s more than a hint of Teddy Roosevelt’s maxim about “speaking softly and carrying a big stick” underpinning the “New Foundation” speech: even as Carter expressed optimism about ongoing nuclear arms reduction talks with the Soviets, he emphasized the primacy of America’s nuclear arsenal in shaping foreign policy:

…just one of our relatively invulnerable Poseidon submarines – comprising less than 2 percent of our total nuclear force of submarines, aircraft, and land-based missiles – carries enough warheads to destroy every large- and medium-sized city in the Soviet Union. Our deterrent is overwhelming, and I will sign no agreement unless our deterrent force will remain overwhelming.

As Jordan consults with the workers, the Carter Administration seems to have put little thought into the contradictions between valorizing a strong nuclear force and hoping to secure a future for the next generation. The workers, however, seem a little reticent about the consequences of that choice. One asks Jordan what the Administration planned to use as a “cornerstone” for the New Foundation: Jordan replies, offhandedly: “I dunno. I guess our strategic capability.”

“You’re the boss,” comes the contractor’s reply. “‘Course, if that goes, everything else will, too.”

It was in the service of checking the Soviets in the Middle East that Carter unflaggingly supported the Shah of Iran and his torture state until the very end, and as it turns out, the geopolitical question that spelled doom for Carter’s vision of a “New Foundation” upon which to build America’s future – as well as his reelection hopes – wasn’t a shortcoming in America’s “strategic capability,” it was events unfolding in Iran. There, much like Trudeau’s version of the New Foundation, the Shah’s regime was collapsing in on itself. A week before the State of the Union, the Shah fled Tehran, never to return; a week later, the Ayatollah Khomeni returned to Iran from exile in France, setting in in motion the final fall of the Pahlavi regime and the transformation of Iran from a monarchy to an Islamic Republic.

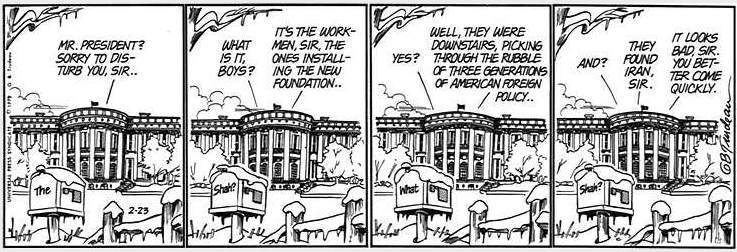

The penultimate installment in the “New Foundation” sequence brings Iran back to Doonesbury for the first time since the February 1978 sequence about the Shahbanou Farah’s appearance at a NYC society gala. The strip sees the contractors barging in on Carter with some bad news: while “picking through the rubble of three generations of American foreign policy,” they’d “found Iran.” “It looks bad, Sir” one of the contractors tells Carter. “You better come quickly.” Things indeed “looked bad” in Iran, and an apparent inability on the part of American policymakers to understand how “three generations of American foreign policy” could come back to bite the United States in the rear end was about to have serious consequences for the country as a whole, as well as Carter’s hopes for a second term.

The “three generations of American foreign policy” that helped doomed Carter’s building project began in 1953 when the CIA sponsored a coup against Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadeq and reinstalled the Shah after Mossadeq had nationalized a British-owned petroleum company. In the decades that followed, Iranian oil and the country’s critical location between the Arab world and the USSR gave American foreign policymakers plenty of incentive to cultivate close ties with the Shah. America provided billions of dollars worth of military aid to the Shah’s corrupt and abusive regime. Given the central role that Iran played in America’s Cold War strategic calculus, (not to mention the central role that post-revolutionary Iran would come to play in American foreign policy-making), the troubles brewing there drew perhaps less attention than they could have. According to one analysis of network television news programming, even though this critical American partner had been becoming violently unstable since before Carter’s New Year’s Eve 1977 Tehran visit, in 1978 the country merited less than three minutes’ worth of reporting a week. Reflecting that lack of attention, Carter glossed over the country in his address, mentioning it once, along with “Nicaragua, Cyprus, Namibia, and Rhodesia,” in a list of countries where the US was “working for peaceful solutions to dangerous conflicts.”

GBT would be the first to disavow any predictive dimensions in his cartooning, but he couldn’t have been any more accurate with his depiction of Iran as a critically overlooked dynamic that would soon take up much of Carter’s attention – as well as his own. While Iran went unmentioned in Doonesbury as its revolution and descent into theocracy unfolded, once the new regime was in place, GBT incorporated the unfolding disaster there into several of Doonesbury’s recurring settings, including Walden College reunions, Mark’s campus radio show, and nightly news screenings at Walden Commune. He also sent two regular cast members, Duke and the Rev. Scott Sloan, to Iran on separate missions, each unsuccessful in its own way.

That said, the “New Foundation” sequence isn’t worth an extended look simply because it happens to hint at what may be coming on the front page or on the comics page, but because it represents an important development in Trudeau’s cartooning, one that saw him digging more deeply into the medium’s ability to take the reader beyond “the arbitrary state of awareness we are taught to regard as reality” as he engaged in sharp political satire.

A while back, I wrote about the story of B.J. Eddy, the White House lawn’s “Head Tulip,” who had been unceremoniously stripped of his duties by Carter’s transition team following the 1976 election. Trudeau, looking back ten years after the sequence ran, saw it as a return to satirical form after a year in which he’d felt frustrated with his writing process. What made the arc work for Trudeau was that let him do what cartooning is particularly suited to do: help readers connect with “nonordinary realities” in ways which reveal how the “real world” in which they are mired actually works, a state of awareness that normally “seems beyond the capacities of every practicing adult.” Between Zonker’s excursions into more whimsical spaces and Duke’s nightmarish visions, a basic appreciation for weirdness has always been central to Trudeau’s work. That said, much of GBT’s explicitly political work of the 1970s tended to avoid extended explorations of the territory outside the realm of consensus reality. The B.J. Eddy strips asked readers to spend a week in a world in which talking perennials enjoyed the same level of public awareness as prominent politicians in order to understand a dig at how Carter relied on empty symbolism to frame his incoming administration as a clean break from the crimes and dishonesty of its predecessors.

The next extended Doonesbury sequence that deployed a dose of sheer unreality in service of political satire was the “New Foundation” arc. As with the B.J. Eddy strips, Trudeau didn’t rely on outlandish visuals to achieve a surreal effect. The B.J. Eddy sequence mostly unfolds with the reader peeking in on Zonker and his plants watching coverage of the story on television. We see Zonker’s plants commenting on developments close to their interests, but that’s the extent of the visual weirdness involved. The “New Foundation” series again finds Trudeau relying on sharp writing, trusting his readers to connect with a parallel/“nonordinary” reality in order to envision the unfolding weirdness. MacNelly’s metaphorical depiction of Carter’s vision is relatively staid and literal, but by not showing what’s actually happening on the construction site, Trudeau’s take prompts readers to travel inwards and imagine their own worst version of a sprawling, rickety structure falling apart as panicked workers try to corral the damage.

Trudeau relies on text to convey the madness unfolding on the job site, but the strips’ visuals sharpen his criticism of the Carter Administration. At first glance the “New Foundation” arc seems almost completely static, with all twenty-four panels across six days’ worth of strips featuring the standard drawing of the White House exterior. A closer look shows Trudeau injecting additional layers of commentary courtesy of shifting depictions of the foreground focal point, the White House mailbox. When the workers mention having “put up a structure of peace” for Kissinger, the mailbox shakily tips to one side, a hint that, like the negotiated settlement in Vietnam that earned Kissinger his Nobel Peace Prize, Carter’s fundamental assumptions aren’t built on solid ground. When Jordan and the workers discuss using America’s “strategic capability” as a cornerstone for the foundation, the four mailboxes are adorned with the sum of $532,000,000,000. The number, rendered three digits per panel, represents the size of the budget that Carter presented to Congress after delivering the State of the Union: putting the figure in a strip focused on “strategic capability” is a nod to liberal critiques that Carter was increasing military spending at the expense of helping the poor. When the workers discover Iran buried under “the rubble of three generations of American foreign policy,” the four mailboxes display a message noting that the Carter Administration had finally abandoned Iran’s monarch: “The Shah? What Shah?”

The mailbox gag in the sequence’s final strip is especially cutting. The sequence ends with a “new metaphor … rising out of [a] pile of old frameworks.” A Carter aide asks Press Secretary Jody Powell “Can we keep him? Can we?” like a kid who’s found a puppy. It’s Trudeau taking another dig at the Carter Administration’s fondness for political symbolism, but the mailbox in the last panel presages some ugly political maneuvering on the horizon. In the first three panels, the name on the mailbox is “Jim,” but by the last panel, when it’s clear that the New Foundation is at heart little more than another empty gesture from Carter’s White House, it reads “Ted?” There was long-standing animosity between Ted Kennedy and Jimmy Carter, and Carter had long speculated that Kennedy might move to replace him on the Democratic ticket. Before the year was up, Kennedy would announce that he was running for President.

It would be another eighteen months before Trudeau next dedicated another week’s worth of strips to digging into comics’ more transcendent qualities in the service of political commentary, with a sequence that got him into a bit of trouble, the infamous “In Search of Reagan’s Brain” arc from October 1980. But before we get there, there’s a revolution, Duke’s botched bagman operation, and a hostage crisis to get through.

Stay tuned.