On 26 January 1981, the Montreal Gazette, the newspaper my family subscribed to, ran a front-page story about a comic strip that, at the time, I, like most young readers, had always skipped over on my way to Peanuts or B.C. because it was just too damn wordy. The news: Doonesbury’s Uncle Duke, last seen facing an Iranian firing squad and presumed dead, was alive and would be returning home along with the 52 Americans who had been held hostage following a takeover of the United States embassy in Tehran by radical students more than a year earlier. A comic-strip plot twist becoming front-page international news recalls a bygone era, when newspaper comics still mattered. In 1929, cartoonist Sidney Smith killed off a character in The Gumps, one of the most popular strips of its time: the Chicago Tribune had to hire extra staff to deal with a flood of letters from distraught readers. Forty-odd years after the Gazette put Duke on the front page, the newspaper comic strip is essentially dead as a broadly-shared cultural experience.

The Iranian hostage crisis, unfolding only a few years after America’s disastrous retreat from Vietnam, combined with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, crippling energy prices and a serious economic downturn sharply undermined American national confidence, setting the stage for Jimmy Carter’s 1980 reelection defeat. After a brief diversion looking at Doonesbury and rock’n’roll, let’s return to Garry Trudeau’s coverage of Carter’s presidency, focusing on events that played a substantial role in both Carter’s defeat and Duke’s twisted storyline: the Iranian revolution and the subsequent takeover of the United States embassy in Tehran.

Trudeau was sharply critical of how, both on the campaign trail and in office, Carter exploited political symbolism. In the Doonesbury White House, Carter’s fondness for symbol over substance culminated with the 1977 appointment of Duane Delacourt as Secretary of Symbolism, a Cabinet position dedicated to creating political symbology; as part of its mission the new department would “[encourage] the average American to take part in the symbol-making process.”

Carter’s fondness for symbolic gestures helped shape his foreign policy approach. As a candidate, Carter envisioned a United States foreign policy built on promoting human rights, one standing in stark opposition to a “realpolitik” approach in which political expediency, more than shared moral visions, dictated American diplomacy. Soon after Carter’s inauguration, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance asserted that the United States would “speak frankly about injustice, both at home and abroad.” Released a year after Carter took office, Presidential Directive 30 codified the new importance of human rights in American foreign policy, tying economic and military aid to recipient countries’ respect for their citizen’s fundamental rights.

Trudeau understood from early on that politics as normal was likely to trump any stated preference for policies based on human rights. Within a few months of Carter taking office, the massive human rights abuses carried out by one of America’s closest Mideast allies, Shah Reza Pahlavi’s Iran, became a recurring theme in Trudeau’s cartooning, revealing a sharp hypocrisy at the heart of Carter’s approach to foreign affairs, an approach that, like much of Carter’s commitments, GBT ultimately found to be essentially symbolic.

Trudeau’s critiques of Carter’s turn towards a diplomacy grounded in human rights overlapped with a new storyline about a figure who’d contributed enormously to making that shift seem necessary, if not practical or likely – former National Security Advisor and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, architect of numerous international crimes including the bombing of Cambodia and the 1973 coup against Chile’s democratically-elected President Salvador Allende. In February 1977, Kissinger joined the faculty of Georgetown; on the funny pages, Kissinger’s freshman foreign-affairs seminar became a regular Doonesbury setting (one I’ll dig into at length once I’ve finished with the Carter stuff). On the first day of class, Kissinger implicitly attacks Carter’s re-orientation of American foreign policy, asserting that “the only practical way to insure world order is to base relations on how adversaries treat us, not their own people.”

“But Dr. Kissinger!” asks a student. “What about human rights?!”

Kissinger’s reply: “Human rights! Human rights! I’m sick to death of hearing about human rights! What do you want anyway – peace or human rights?!”

One of Duane’s first tasks upon becoming Secretary of Symbolism concerned the White House’s new focus on human rights and helped set up the story of the impending upheaval in Iran and of Duke’s imprisonment and eventual liberation. On 7 April 1977, Vance called Delacourt to ask for help symbolizing the administration’s “seriousness” about its commitment to international human rights. Duane’s solution: a “human rights award banquet – to honor those nations which still cherish human dignity.” Doubling down on the administration’s apparent aversion to concrete policy expressions, the awards would allow the State Department to “underscore [its] moral positions through inference, instead of through the usual direct reproach.” (The trophies featured “a little guy struggling with his chains” and an inscription from Gandhi.)

A week later, Iran got its first mention in Doonesbury when the country’s ambassador to the United States phones Duane to express his regrets that he won’t be able to attend the banquet. He hopes that his absence won’t cause “too much inconvenience,” and tells Delacourt that he’d “feel just terrible “ if Iran had won.

Duane’s reply: “As would we all, sir.”

If he was truly committed to promoting human rights, Carter surely would have “felt terrible” if Iran had won one of those coveted awards. But Carter, guided by the same priorities that Kissinger had outlined to his students, strongly supported the Shah, because Iran was a vital regional US Cold War ally.

In 1953 the United States and Britain sponsored a coup against Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, who had nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a British firm that enjoyed a monopoly on Iranian petroleum production, and reinstalled Shah Reza Pahlavi. In the years that followed, besides being a supplier of petroleum, Tehran provided the US with sites for radio listening posts and a base for spy-plane missions. In exchange, the US sent Iran billions of dollars’ worth of military aid, no small part of which was intended for use against Iranians.

By the time Carter took office, the Shah’s regime was facing growing dissent from both leftist and Islamic fundamentalist groups. SAVAK, the Iranian state police, brutally repressed opposition to the Shah. In July 1977, the International League for Human Rights condemned the Shah’s regime over mass arrests and torture of dissidents while criticizing the State Department for not being “sufficiently candid in reporting to Congress … on human‐rights conditions in Iran.”

Anti-Shah protests – and police violence against them – were not limited to the streets of Tehran. On 15 November 1977, as the Shah visited Carter’s White House, “the most militant demonstration in Washington DC since the Vietnam War … left 96 demonstrators and 28 police officers injured.” The protests were organized by Iranian students in the US. Fearful of repercussions for their families back home – a possibility given the links between the CIA and SAVAK – the students wore simple paper masks to conceal their identities and to “symbolize the oppression they felt even outside Iran.”

On New Year’s Eve 1977, six weeks after violent anti-Shah demonstrations left the smell of tear gas lingering on the White House lawn, Jimmy Carter visited Tehran as part of a whirlwind world tour. At a state dinner, Carter, revealing the profound gap between his stated commitment to promoting international human rights and his support for brutal regimes when it proved politically useful, praised Iran as an “island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world,” and lauded the Shah for the “respect and the admiration and love” the Iranian people had for him.

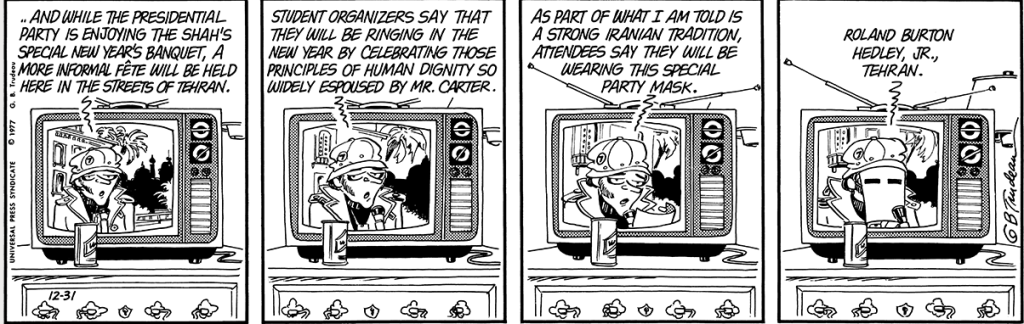

SAVAK ensured that protests on the streets of Tehran were minimal during Carter’s visit, but on the comics page, Trudeau used bitter sarcasm to draw attention to the growing anti-Shah demonstrations. Doonesbury’s resident ABC correspondent Roland B. Hedley Jr. predicted that Tehran student organizers would be “ringing in the new year by celebrating those principles of human dignity so widely espoused by Mr. Carter” – a type of celebration that, were it to actually occur, would surely bring down the heavy hand of the Iranian state. The students, Hedley continues, would, in keeping with what he’d been told was an “Iranian tradition,” be “wearing this special party mask”: He then dons a paper mask similar to the ones seen in the streets of DC only weeks before.

The strip exemplifies Trudeau’s long history of satirizing news media through Hedley’s journalistic incompetence, captured here in his credulity about the meaning of the masks. Beneath that, there’s a sharp attack on Carter’s hypocrisy about holding America’s partners accountable for their failures to uphold the very “principles of human dignity” that he had espoused as a candidate and as President.

While the “traditional” paper masks may have been largely absent in front of the Shah’s palace on New Year’s Eve 1977, two weeks later, emboldened by Carter’s New Year’s Eve endorsement, the Shah’s regime struck back at dissident elements as SAVAK clamped down on protestors in the holy city of Qom with a new ferocity, killing 20 and injuring 300. Historians of the Iranian Revolution point to the escalating cycle of protest and oppression that began in Qom as the beginning of the end of the Shah’s regime.

Only a few days after the violence at Qom, the Shah’s wife, the Shahbanou Farrah, was the guest of honour at a dinner of the Asia Society held at the New York Hilton Hotel; Henry Kissinger was among the attendees. Even though the city spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to pay extra officers to keep demonstrators at bay, the Times reported that the Shahbanou’s speech was interrupted on several occasions by protestors screaming “Down with the Shah!—he’s a murderer!” Outside the hotel, anti-Shah demonstrators again wore paper masks to conceal their identities from Iranian agents.

Two weeks later, Dr. Kissinger was, on the comics page at least, held to account by his students for attending the event. The students came to class wearing paper masks “to symbolize [their] solidarity with the repressed peoples of Iran.” One asks Kissinger if he’s familiar with Doctors Rassouli, Rezvan, Shadi or Tehrani, the “master torturers at Komite prison in Tehran.” When Kissinger says he doesn’t know the men, the student reveals that the Shah’s torturers call themselves “Doctor” “because they feel the title gives them an air of authority and professionalism.”

It would seem that Kissinger’s students, and presumably Trudeau, had read a recent book by the Iranian dissident poet Reza Baraheni. In 1973, Baraheni was arrested by the Shah’s regime; he was imprisoned and tortured for 102 days before being exiled to the United States. His 1977 memoir, The Crowned Cannibals: Writings on Repression in Iran, chronicles his experience in Komite prison, the same facility mentioned by Kissinger’s student. (The book features an introduction by the novelist E.L. Doctorow, whom Trudeau has named as an important influence on his own work.) The men whose names are put to Kissinger all appear in Baraheni’s harrowing description of the violence those men inflicted upon him and his fellow prisoners. Baraheni recalls how the men who tortured him all called themselves “doctors” or “engineers” because they saw themselves as “professional technicians.” In one particularly dark description of a violent interrogation, one of the torturers explains that he insists on being called “Professor” because he “[thirsts] for knowledge.”

Dr. Kissinger may seem shocked at the revelation that Rassouli et. al. aren’t “real doctors,” but lurking beneath the gag is an acknowledgement that the American foreign policy Establishment is well aware of the situation in Iran – and basically accepts the broad strokes of the situation.

That evening, Kissinger’s students don their paper masks to join the protests in front of the hotel. (When Roland asks them why they’re hiding their identities given that they have no “relatives or loved ones in Iran” to protect, the reply is that they’ve “got mid-terms coming up.”)

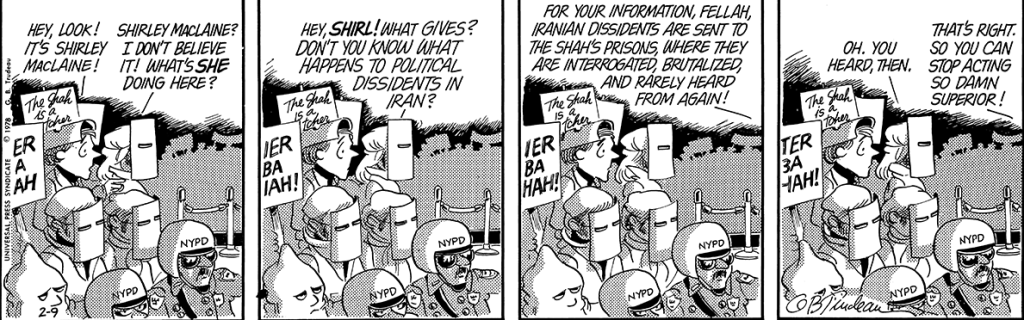

There’s a deep cynicism in Trudeau’s cartoons about the Shahbanou’s NYC appearance. The name of the organization hosting the Shah’s wife becomes the “Friends of Exxon Society,” a jab at how the realities of the oil economy dictated American diplomatic priorities. Trudeau also attacks elements of the broader US Establishment who had hypocritically made peace with the Shah’s brutality while embracing Carter’s progressive vision. NYC’s Democratic mayor Ed Koch denies “endorsing political repression in Iran” with a distracting claim about conditions in the USSR. Shirley MacLaine, who had performed at Carter’s “New Spirit” inaugural concert, was a friend of Princess Ashraf, the Shah’s sister: she writes in her memoir about being a frequent guest at the Iranian ambassador’s residence. “The Iranians,” she recalls, “loved movie stars and hearing the latest gossip.”

In Trudeau’s account of the banquet, MacLaine becomes a stand-in for elite indifference to the plight of Iranian dissidents. The students taunt the celebrities arriving to attend the dinner: when MacLaine appears, they ask her if she “[knows] what happens to political dissidents in Iran.” Her dismissive reply underlines the extent to which Carter’s allies had no problem with his hypocritical support for the Shah:

“For your information, fellah, Iranian dissidents are sent to the Shah’s prisons, where they are interrogated, brutalized, and rarely heard from again.”

The Shahbanou’s storyline ends with Trudeau calling out the news media for its complicity with the Shah’s regime. As the dinner is interrupted by another protestor screaming “The Shah is a murderer!,” Roland describes the man being “wrestled to the ground by four decorum-minded Iranian security agents.” His description of the scene continues:

“Presumably to stifle his outbursts, a napkin is being stuffed in his mouth, an unnecessary measure in this reporter’s judgment, as a nasty rabbit punch has already taken away his wind.”

Roland, as the waiter offers him an espresso, prompts ABC News anchor Barbara Walters to pick up the story:

“For the empress’ reaction, up to you at the head table, Barbara!”

Barbara Walters may or may not have been at the head table that night – more on that below – but she had a long history of friendship with the Shah and his family. The political scientist James Bill names Walters, along with other prominent journalists like David Brinkley, as part of a network of political, cultural and intellectual figures whom the Shah’s regime counted on to promote its interests in the US. Bill notes that Walters “introduced the leaders of the royal family to the American public in a very positive light,” conducting several interviews with the Shah and his wife, and received lavish gifts from the Iranian embassy, including “caviar, Cartier silver, and … a diamond watch.” GBT didn’t pull his punches while criticizing the media’s role in shaping the Shah’s image for the American people, naming one of the country’s most popular television journalists as a close associate of a regime unafraid to use violence in a public way in order to maintain its grip on power.

In an analysis of how American TV news covered the Iranian hostage crisis, James Larson points out that throughout much of the 1970s, US television journalists “depicted Iran as a strong ally and supplier of oil, needing support principally in the form of US arms.” This dynamic only began to shift around the time of the Shah’s November 1977 visit to DC, though reports on SAVAK’s increasingly-difficult-to-ignore brutality were balanced by reporting that continued to frame the Shah as “a staunch friend and ally of the United States.” That said, Iran remained a relatively insignificant topic in American news reporting until the upheavals of 1979, representing less than two percent of the international news stories carried on American news programming.

Knowing that, it’s not surprising that the Shahbanou’s NYC visit received limited coverage in the papers at the time (nor does it figure prominently subsequent historical scholarship). Aside from a mention of Kissinger’s presence at the banquet in the one NYT story about the evening, I’ve been unable to find concrete references to Walters or MacLaine being at the Hilton that night. But even if MacLaine or Walters weren’t there, it’s clear that their associations with the Shah and his family were well-known enough in some circles to merit some very pointed attention from Trudeau. Trudeau dedicated two weeks’ worth of strips to an event that received little public attention, revealing his profound discomfort at how the Carter White House, and the broader American Establishment, was willing to accept the Shah’s abuses of his people –at home and abroad – because his continued reign suited their purposes. Having read Baraheni’s horrific descriptions of life under the Shah – Garry obviously read the book very closely, closely enough to call out Baraheni’s torturers by name – I get why.

Next time out: the Revolution finally comes, and it turns out very badly for the people of Iran, for American oil interests, and for Doonesbury’s favorite moral degenerate.

Stay tuned.

One thought on “Interrogated, Brutalized, and Rarely Heard from Again: Doonesbury Goes to Iran.”