Last time out looking at Doonesbury in the Carter years, we focused on how Jimmy Carter’s early presidency was defined by symbolic gestures like cutbacks to limos for government officials, a live presidential phone-in, and wardrobe choices calculated to reinforce his “down home” vibes. This time, a look at how Garry Trudeau wrote about one of Carter’s key symbolic moves, creating an image as the first “rock’n’roll president.”

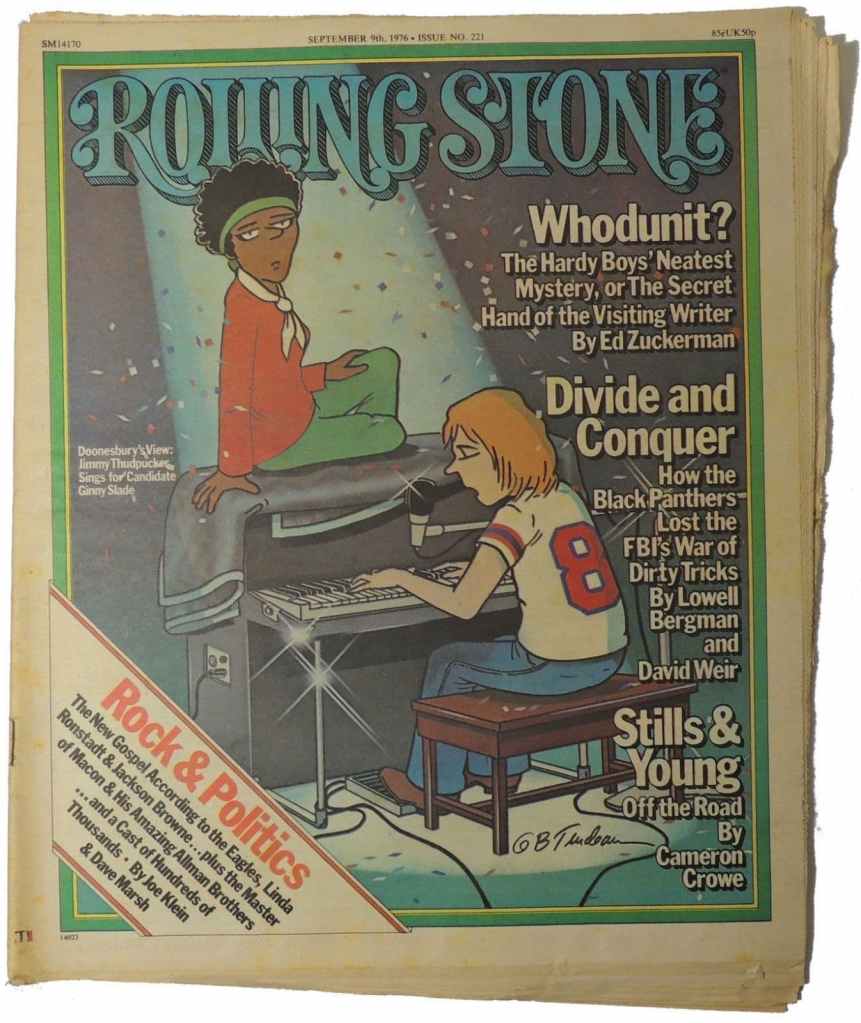

Doonesbury was, arguably, the first mass-market “rock’n’roll comic strip,” or at least the first to feature sustained commentary on rock culture. Trudeau earned a degree of rock cred when he made the cover of the Rolling Stone in August 1975, when the magazine ran an excerpt from Tales from the Margaret Mead Taproom, a book GBT wrote with Nicholas von Hoffman about a trip the pair took to American Samoa shortly after Duke’s reign as the territory’s Governor. A year later, Trudeau drew his second RS cover, this one featuring Congressional candidate Ginny Slade sitting on Jimmy Thudpucker’s electric piano as Doonesbury’s resident rock legend plays for her.

The cover story had nothing to do with the comics. Joe Klein and Dave Marsh examined the growing ties between rock and politics. Post-Watergate reforms curtailed how much cash individuals could contribute to candidates, but there was a loophole: there was no limit on the time and labor one could contribute to a campaign by, for example, being a rock star and playing benefit gigs that could net tens of thousands of dollars for a campaign in a single evening. Like his real-life counterparts who played for people like Carter and California Governor Jerry Brown, Thudpucker contributed to Slade’s campaign by playing a fundraising concert and recording a track to promote her candidacy.

RS saw a crucial difference between these developments and the rock-star activism of the 1960s, when musicians were more likely to lend their voices to politics out of a genuine commitment to issues like ending the war: by 1976 “the real relationship was between the music-business executives and the politicians,” with artists being instrumentalized by businessmen seeking to foster ties with the political establishment. Paul Simon described musicians as “people to be used and discarded” … bringing the kids in for the music, then giving the money to a political candidate.”

“I never thought we’d have influence on the candidate,” Simon noted. Indeed, the ties that music-biz execs were building with politicians were meant to create a friendly environment for policies friendly to big record labels, including tax breaks and stricter copyright laws.

Klein and Marsh noted that Carter had raised $350,000 with the help of his rock-star friends, but his rock connections ran deeper than the typical dealings between politicians and music-business executives. A key element of Carter’s image as a politician in tune with a younger generation was his genuine love for rock and outlaw country music and the people who played it. Mary Wharton’s recent documentary, Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President examines Carter’s relationships with musicians like Willie Nelson, the Allman Brothers, and Crosby, Stills and Nash. Carter staffer Peter Conlon argues that Carter’s acceptance of “people and their frailties”– a central theme of Carter’s landmark 1976 Playboy interview – left him well-positioned to change “the relationship between rock and roll and political power.” Typically, issues like drug use forced most politicians to keep rock culture at arm’s length; Carter’s ability to meet people where they were allowed him to associate himself with figures who were relevant to a younger electorate while not risking losing an air of propriety necessary to appeal to more uptight voters.

One rocker played a particularly crucial role in shaping Carter’s worldview and how he presented it to the American public: Bob Dylan.

The Playboy interview and Hunter Thompson’s 1976 Rolling Stone profile of Carter both feature Carter’s reflections on how Dylan helped shape his outlook. Carter told Playboy that his sons had been Dylan fans as he was getting into politics; the songs he’d heard around the house helped him understand how their generation was thinking about “civil rights, criminal justice, and the Vietnam war.” Thompson recounts Carter naming songs like “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, “The Times, They Are a-Changin,’” and “Like a Rolling Stone” as having taught him to “appreciate the dynamism of change in modern society.”

When Dylan and the Band played in Atlanta in January 1974, Carter invited the troupe to the governor’s mansion. Dylan recalls how “the first thing” Carter did when they met was to “quote [his] songs back” to him; the experience helped Dylan realize that his music had “reached into … the establishment world.” In Playboy, Carter recalled how Dylan apparently disavowed having “any inclination to change the world.” The question of Dylan’s role as the “voice of a generation” underpins Doonesbury’s take on the first encounter between the rock star and the new President.

On 14 February 1977, a few weeks before Carter’s “Dial-a-President” media stunt, his Doonesbury incarnation fielded calls from random Americans. One caller asks Carter why he didn’t quote Dylan more often; Carter agrees that he should. “As you know, Miss,” he says, “Bob Dylan’s music has a lot to teach all Americans about hypocrisy and social injustice.”

Carter then instructs Chief of Staff Hamilton Jordan to “call Bob out in Malibu for a quote right now.”

“Hello, Bob? Jimmy Carter here!”

“Hey man,” Dylan replies. “Do you have any idea what time it is?!”

We spend the rest of the week hanging out in Malibu with Jimmy Carter’s “favorite rock and roll legend” as his house guest, fellow rock legend Jimmy Thudpucker, eavesdrops on his conversation with the President.

***

Ladies and Gentlemen: Jimmy Thudpucker!!!!

I’ve always found it curious that, for a cartoonist so closely focused on campus life and youth culture, GBT didn’t really satirize the world of rock’n’roll during the first few years of Doonesbury’s run.

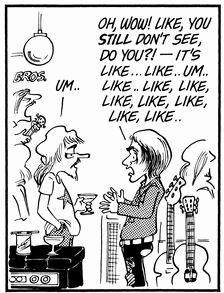

There are a few exceptions, notably Duke’s ongoing feud with neighbor John Denver. My favorite early-Doonesbury rock encounter is from July 1974, when Zonker drops in on Duke at the offices of Rolling Stone, and editor “Jawn” Wenner throws a party in his honor. There, Zonker meets Neil Young, and tells Young how much he loved his last album (…which would have been 1972’s Harvest, unless somehow Z heard an advance pressing of On the Beach, which came out a week after this strip ran). He asks the rocker “What were you trying to say?”

(This is of course, the worst question to ask an artist, because if they could have said “what they were trying to say” in a pithy sentence or two, they wouldn’t have gone to the trouble of making a record or drawing a comic strip for half a century.)

Young is flummoxed and becomes increasingly frustrated as he tries to articulate his vision for the project:

I was, like, y’know, getting off on, uh, energy … Yeah man, don’t you see? It’s like part of the karma, like, energy, you dig? … Oh, wow!, like you still don’t see, do you?! It’s like…like…um…like…like, like, like, like, like, like, like … Oh, wow…

While the idea of meeting someone who’s way further gone than Zonker gets a chuckle, Steve Allen had been doing gags about inarticulate rockers for a long time before Trudeau drew this. A year later though, Trudeau began writing about rock musicians with more insight and complexity. In September 1975, Duke sent Zonker to cover a Gregg Allman session for Rolling Stone. When Allman calls in sick, the producer – a dead ringer for recording legend Tom Dowd, who worked extensively with the Allmans – invites Zonk to sit in on a Jimmy Thudpucker session.

Jimmy Thudpucker is loosely based on Jackson Browne (The Doonesbury Chronicles’ epigraph is a Browne lyric; The Cartoonist is a fan). There’s a physical resemblance, and, like Browne’s, Thudpucker’s music seems to fit somewhere between the laid-back folk stylings of James Taylor and the harder-edged rock Neil Young was playing in the mid-70s. Like Browne, Thudpucker is a regular on the benefit gig circuit. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Browne comes off as being interested in using his talents at a more grassroots level: even as he played for big-name candidates like Jerry Brown, the Rolling Stone issue that featured Marsh and Klein’s article also featured a story about Browne’s recent concert for a utopian techno-eco-settlement in the Arizona desert.

While Rolling Stone saw rock stars being cynically manipulated into electoral politics, Thudpucker’s no political naif. At the session Zonker observes, Jimmy records a song about the Mayaguez incident (…a crisis that unfold during Duke’s time in Pago Pago after Cambodia seized a US ship) and a tune praising Morris Udall (an Arizona representative best remembered for his environmental work and for being the first Democratic congress-critter to speak out against the Vietnam War ). When Zonker approaches Jimmy to play a benefit gig for Slade’s campaign, the singer grills his new friend about her positions on issues ranging from migrant farm workers, to gay rights and illegal aliens. Later, when Joanie approaches Jimmy to record a song for the campaign, she asks him to come up with “some catchy lyrics about her strong positions on busing and abortion.”

In contrast to that one-dimensional caricature of Young, in Thudpucker GBT introduced a complex character who gave him a voice to spoof the music and musicians central to Baby-Boomer identity. Jimmy isn’t nearly as spaced out as GBT’s version of Young, but he’s imbued with an endearing innocence. Rendered with the wide eyes sported by children and tender-hearted if somewhat naive characters, Thudpucker embodies genuine sensitivity: he’ll reduce a hardened studio pro to tears with a new love song, and then cut short a “very scheduled, very expensive” session to make it back home for dinner with his wife.

But that sensitivity is contrasted by deeply-seated cynicism and disillusionment. He detests having to perform a contractually-obligated “heavy dues song,” not wanting to be cast as one of those “rockers who whine about how they had to suffer on their way to the top” when he’d never experienced anything more traumatic than an appendectomy. When Bill Graham tries to book him as a “friend” for a “Leon Russel and Friends” concert, he dismisses the people involved as “egomaniacal creeps” and tells his manager: “I’m tired … I want to go back to college.”

Jimmy does the gig for $25,000 and a percentage of the gate.

Jimmy’s cynicism underpins the Carter-meets-Dylan strips. In GBT’s world, Carter’s no passionate Dylan fan; instead, like the executives and politicos RS described, he instrumentalizes a cursory knowledge of the singer’s work to foster his image. Dylan, meanwhile, is revealed to be more interested in cashing in than in being the Voice of a Generation. When Carter calls, Dylan’s in his jacuzzi, leaving Jimmy to chat with the President. Carter tells Jimmy that he needs a quote, but can’t seem to quite put his finger on what song might fit the bill. He thinks it’s from “that album which has his hair all lit up from behind,” referring, of course, to the most basic of all Dylan releases, his Greatest Hits album. He then goes on to recite a hodge-podge of misheard excerpts from some of Dylan’s most popular tunes:

“Now you don’t know what’s happenin’, doooo you, Mister Rollin’ Stone/Oh, yeah, the twisted organ grinder criiies….”

Jimmy isn’t fooled. When Dylan asks him if he had been “co-opted” by the President,he replies: “Hardly. He picked your dumbest song.”

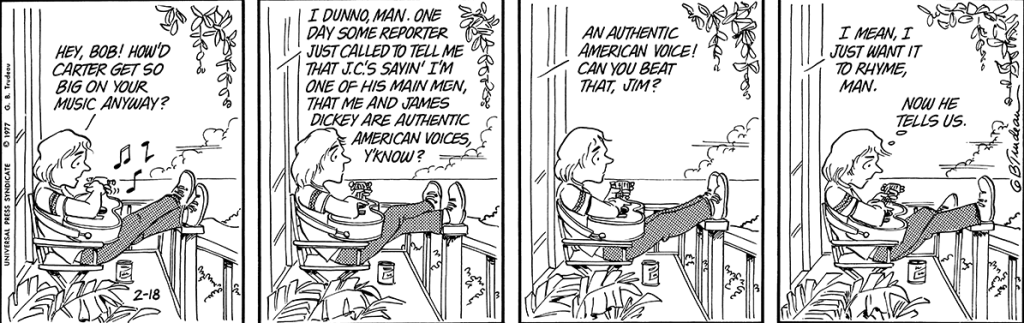

While Dylan is wary of being “co-opted,” he’s also transparent about what he thinks of Carter calling him (…and poet/novelist James Dickey, who read at Carter’s inauguration) an “authentic American voice.”

“Can you beat that, Jim?” he chuckles. “I mean, I just want it to rhyme, man.”

***

I speculated in a previous post that the election of Jimmy Carter presented Trudeau with a challenge, in that he would have to, after six years of mocking Republican presidents, including the man who set a standard for political corruption and malfeasance that lasted for two generations, turn his pen on someone from the other side. By leaning hard into skewering Carter’s hard-won image as a “man of the people” and portraying him as, like any other politician, a cynical manipulator of political symbology, GBT demonstrated that he was up to the task.

The Dylan strips in particular, and Jimmy’s story more generally, also reveal Trudeau’s willingness to poke fun at rock music as it became increasingly commodified, absorbed into the mainstream, and instrumentalized in order to advance the interests of the rich and powerful, even as artists like Jackson Browne tries to maintain some sense of connection to more grass-roots sensibilities. Next time out, I want to take a break from GBT’s take on Carter and dig a little more deeply into his rock satire, with a deep dive into a couple of Doonesbury rarities.

Stay tuned.

***

I wrote a companion piece to this essay in which I get personal about how Dylan’s lyrics have helped me make sense of my experience as a long-haul Stage IV cancer patient. Read it here.

2 thoughts on ““Catchy Lyrics about Busing and Abortion”: Doonesbury, Rock’n’Roll, and Politics.”