Bob Dylan’s on the road again, playing more dates on his Rough and Rowdy Ways tour. Hope springs eternal that God will allow for the possibility that both Mr. Dylan and I will remain alive long enough for our paths to cross at some local concert hall sometime soon.

I’m currently writing something about some strips that The Cartoonist did about Jimmy Carter’s reputation as “the first rock’n’roll president”; Dylan is a key character in the storyline. Anyone who knows me understands how geeked I am about this: my favorite comic strip spoofing one of my favorite musicians. I’m having a lot of fun digging into these strips.

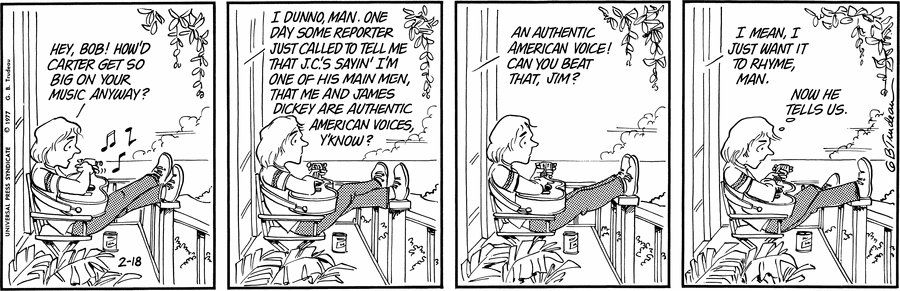

The strips in question focus on a phone conversation between Carter and “the rock and roll legend.” Doonesbury’s version of Dylan appears only as an off-panel voice; the arc’s final punch-line is one of my personal “Top-Five Doonesbury Moments.”

Dylan’s reputation as a “voice of a generation” is at best exaggerated, and he knows it. Maybe he “just wanted it to rhyme,” but he’s content to let people continue to have the wool pulled over their eyes.

I mentioned this strip in my intermittent correspondence with The Cartoonist, who responded that he always saw Dylan’s genius not so much in particularly trenchant insights into his times as much as in his ability to, in his best work, string together aesthetically-pleasing combinations of words that are often more effective at evoking a personal response in listeners than they are at providing explicit insights. The Cartoonist noted that he was very pleased to have had his take on Dylan validated during a recent viewing of a documentary film.

In Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home, Joan Baez recalls a young Bob Dylan laughing about the meanings attached to his writing:

He would say, ‘A bunch of years from now, all these people, all of these assholes are gonna be writing about all the shit I write. I don’t know where the fuck it comes from! I don’t know what the fuck it’s about! And they’re gonna write what it’s about.’

The evocative, open quality of Dylan’s writing has, for much of my life, helped me get a handle on questions and feelings that lay just outside the limits of my meager abilities with language. A complicated dynamic in an intimate relationship; a stress reaction to a new situation; the quotidian joys and struggles of being human: when I couldn’t find the words to freeze ephemeral notions into concrete ideas I could actually think with, quite often a Dylan lyric helps me grasp something hovering just beyond the reach of my own words.

***

That I can again, after a few months away, access my usual enthusiasm for my niche interests tells me that I’m in reasonable shape, notwithstanding recent developments to the contrary. Last month, I underwent my fifth cancer surgery in three and a half years. My crack equipment crew remains confident that I may well be around for a good while yet; they also remind me that it’s a bloody miracle that I’m still here and that miracles aren’t reliable. “Past performance is no guarantee of future results.”

During my first encounter with cancer in 2020-21, I began to notice tingling in my hands and feet, an expected side-effect of the particular chemotherapy they used on me. It got gradually worse: I began dropping things; I couldn’t play guitar as well as I used to; most worryingly, I tripped and fell a couple of times when my feet felt like they had fallen asleep. My oncologist was blunt: I would have to live with chemo-induced neuropathy for the rest of my life.

I asked a nurse if this meant I should start using a cane for stability. “Well,” came her reply, “You can get a cane before you break your hip or after you break your hip. Either way, you end up using a cane.”

On one of my first walks with the cane, I listened to the Bootleg Series release of Dylan’s 1975 Rolling Thunder tour, which features my favorite performance of “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I’ve heard that song hundreds of times over the last 40 or so years, but walking with my new cane, worn down by my treatments and sharply aware of my numb feet, I heard the song in a whole new way.

I was, at the time, starting radiation therapy, which left me with a kind of fatigue unlike anything I’d ever experienced before. I got more worn-out with each treatment: by the end of it I was sleeping about 14 – 16 hours a day. Hellish.

“My weariness amazes me; I’m branded on my feet.”

That got my attention.

And then…

My senses have been stripped. My hands can’t feel to grip, my toes too numb to step, wait only for my boot heels to be wandering…

My hands can’t feel to grip, either. My toes are too numb to step. Beyond that, I can’t feel much of my abdominal area; too many surgeries have left me numb.

My senses have been stripped.

I had to sit down.

Dylan’s lyrics let me more clearly understand my growing frustration with, and alienation from, a body that had already been severely violated, with more violations to come. This was the first step of a process that I’m still struggling with: living in a body that, now broken in some pretty fundamental ways, doesn’t feel like “home” anymore.

These days I’m listening to a lot of Dylan’s 1980s material, and a few songs from that era have taken on particular significance for me, helping me articulate some deeply-felt stuff coming out of my cancer experience that I otherwise might not find the words for.

There’s a new version of “Foot of Pride,” on the Springtime in New York box set:

You’re gonna arrange to see a man tonight who’ll tell you some secret things you think may open some doors.

How to enter the bloody gates of Paradise?

No.

How to go crazy from a carrying a burden that was never meant to be yours

…

And you still thinking that you’re the same person you used to be.

I was definitely not cut out for this particular ordeal: nobody is meant to carry the burden of long-term serious illness. And after all I’ve been through, I sure as hell am no longer the person I used to be. I need reminding of that sometimes, especially when I get frustrated with my unreliable energy levels and other legacies of this experience.

Later, he sings: “From now on, this’ll be where you’re from.”

My experience with cancer, like many traumatic experiences, has fundamentally redefined who l am. This is now “where l’m from,” something as central to my identity as my hometown.

Or even more so.

That said, one of my favorite Dylan tunes from that era briefly points to the possibility of overcoming all of this. I always get a lift when I listen to “Tight Connection to My Heart” and get to the line where Dylan observes that “what looks large from a distance, close up ain’t never that big.”

I mean, I’m here, right? How hard could it have been?

***

My colorectal surgeon explained my situation this way: to beat some pretty lousy odds, we had to follow one path along a deep decision tree. Each decision we made had to be the right one, had to be executed as close to perfectly as possible, and there wasn’t much room for unforeseen complications. If everything went just exactly perfectly, I could beat this thing and live something approaching a normal lifespan.

Ultimately, it’s luck. There’s nothing meaningful I can do to “fight” cancer beyond showing up for my appointments on time and taking the pills they give me.

I just gotta be lucky.

But luck always runs out. Ask the Roving Gambler.

But there is, in that horrible reality, the possibility of something that comes awfully close to liberation. My priorities have shifted radically. The list of things that used to keep me up at night and that I now simply don’t give a fuck about is very long indeed.The anxiety that had done so much to mess with my head and heart for years? Not gone, but no longer my constant companion.

I mean, what’s the worst that might happen? My Brother in Christ, I have stage IV colorectal cancer. The stats, and the lived experiences of people who’ve had this disease, are sufficient evidence that it doesn’t get much worse.

The last stanza of “Tambourine Man” helped me understand that I was free from so much that had, for much of my life, held me back and harmed me. I often feel the most alive on my late-night walks around Vanvouver’s Seawall. I’ll stop at the beach on a clear night, maybe smoke a joint, put in my earbuds, and look at the stars and the moonlight reflecting on the water.

Sometimes, when the mood and the ganja and the music hit in the right way, I’ll dance.

Take me disappearing through the smoke rings of my mind, down the foggy ruins of time, far past the frozen leaves, the haunted frightened trees, out to the windy beach, far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow.

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky, with one hand waving free, silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands, with all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves. Let me forget about today until tomorrow.

Thanks Bob. For making it rhyme, and for taking me far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow. And thanks to The Cartoonist for helping me laugh about it all.

2 thoughts on “Dylan, Doonesbury, and Me”