Something I’ve returned to as I’ve examined Doonesbury during the Carter years is Jimmy Carter’s self-presentation as an “outsider,” an alternative to the lies and corruption that had soured many Americans’ faith in government after the twin crises of Vietnam and Watergate. The story of B.J. Eddy – the Head Tulip from the White House garden who was unceremoniously fired shortly after the 1976 election – showed Garry Trudeau poking fun at how Carter set out to portray his presidency as a clean break from the politics of the past.

I’ve also mentioned how Trudeau was critical of much of his work from 1976, as his main focus that year, Ginny Slade’s congressional campaign, became a dense storyline featuring overlapping dynamics making it challenging for him to develop more fully the individual stories at play, many of which involved newer characters who were becoming regulars. GBT saw the B.J. Eddy arc, built on Zonker’s surreal relationship with his houseplants, as something of a return to form, putting him back in touch with a transcendent sense of whimsy that he felt had been absent from the strip as he juggled topical satire with several “moving parts” in the form of those new faces.

After the election, Rick and Joanie, who started dating during Ginny’s campaign, began learning more about each other (and us about them) as they embarked on their lives together. Rick spent the transition and the first six months of the Carter administration on leave from the Post, writing for People. GBT used that opportunity to weave his critiques of the media’s growing obsession with celebrity culture (notably in an arc about Zonker and Mark’s night at Studio 54) into Rick and Joanie’s developing story. With Rick consigned to covering Ryan O’Neal , it fell on another pair of characters emerging from Ginny’s House run, Lacey Davenport (the eventual winner) and her husband Dick, to do the heavy lifting in Trudeau’s examination of the transition from the Ford to the Carter administrations. I’m not going to dig deeply here into Dick and Lacey’s history or talk about Lacey’s relationship with her doppelganger here on the temporal plane, Representative Millicent Fenwick. Instead, I want to focus on how, over the course of two weeks of dailies and a Sunday strip, Trudeau gave characters who were still somewhat undefined space to reveal themselves in an organic, unrushed way, while still delivering sharp political and cultural observations.

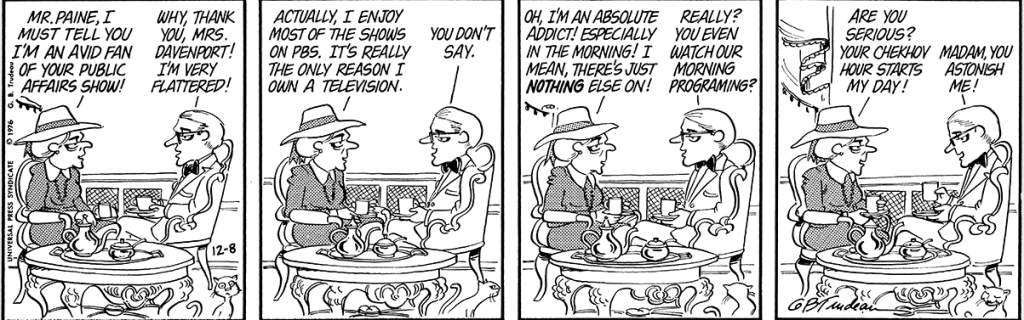

On 6 December 1976 Lacey and Dick reluctantly welcomed a television reporter into their home to interview the incoming freshman representative. Normally, Lacey would “refuse to suffer the indignity” of dealing with television journalism’s “silly electronic pop stars,” but she changes her mind when she realizes that the reporter is Adam Paine, host of The Paine Report, one of her favorite shows on the only station she watches, her local PBS outlet. The strips that follow underline Lacey’s core characteristics, notably her being a stickler for old-fashioned notions of propriety, from her initial concern that the “fellow from PBS” was sufficiently “well-mannered” and “neat in appearance” to her being appalled at a member of the camera crew neglecting to use an ashtray in her home. Beyond her concerns about social niceties, we also learn about Lacey’s small-c conservative tastes: she starts her day watching PBS’s morning “Chekhov Hour.”

With his suckup Ivy-League personality, Adam Paine, whom I’m reasonably certain is a spoof of the typical eggheaded PBS host rather than a caricature of a specific public-television personality, is something of a precursor to a bit player GBT introduced in 1986, T. Hamilton “Trip” Tripler, Sal Doonesbury’s college roommate, “quote boy” to conservative columnist George Will, and later morale officer on the U.S.S. Mercy, a hospital ship where Ray recovered from a nasty leg wound during the first Gulf war. As he caricatures the network’s talking heads, Trudeau takes other friendly jibes at PBS: Lacey’s morning “Chekhov Hour” habit teases the network’s intellectual pretensions; she also good-naturedly complains about how PBS’s ubiquitous pledge drives “make people feel so guilty.”

The interview done, the following Sunday’s strip foregrounds some of Dick’s essential character dynamics, notably his passion for ornithology, the absolute dedication shared between him and Lacey, and something I share with the man, a deep aversion to change. We open with Dick in his trademark straw hat, preparing to move to DC, forlornly bidding farewell to his treasured wrens and thrushes. He’ll miss his birds, but what really worries him is that once he and Lacey get to DC, his fascination with the tufted titmouse will no longer be enough to keep his beloved’s attention as she becomes “swept up in the Washington whirl.” Trudeau delivers a touching moment as Lacey chastises Dick for believing that he’ll be left to “eat little ham sandwiches at the Smithsonian” while she “[lunches] on escargots with Art Buchwald.” Lacey rushes to reassure her husband that her dedication to him will remain steadfast: “After thirty-five years,” she says, Dick should know better than to believe that she would abandon him.

We catch up with Lacey and Dick in early January 1977 as they settle into life in the capital. The arc, which begins as Dick tries to get out of accompanying Lacey to a dinner hosted by Gail Howe, a woman who “presides over the most breathlessly ‘A’ list salon in Washington,” sees GBT deepening our understanding of Dick’s insecurities and the depth of the love he shares with Lacey with observations about DC society and jabs, both friendly and more biting, at the outgoing and incoming presidents.

Salons like Howe’s were a central part of DC’s intellectual and social scene in the decades following the Second World War. In a 1996 article for the New Yorker, Sidney Blumenthal traced the rise and fall of the Georgetown set, where politicians, journalists and intellectuals exchanged ideas and forged connections they used to help shape United States policy. While Blumenthal centers the journalist Joseph Alsop in his account of Georgetown’s Cold-War era heyday, its peak during Camelot and its eventual decline in the 1970s (another victim of the turbulence of Vietnam and Watergate), he also chronicles the critical roles played by elite women like Alice Roosevelt Longworth, Avis Bohlen, and Katharine Graham in creating and shaping the Georgetown scene and the ideas that took place within its tony confines.

Given that she does nothing besides welcome Lacey to her home, I’m reasonably sure that, as with Adam Paine, Gail Howe represents more of a “type” than any particular Georgetown woman. That said, Blumenthal mentions someone who might have been performing the real-world version of Howe’s role as salonnière that evening in 1977: Polly Fritchey, the wife of journalist Clayton Fritchey, whose name appeared on Richard Nixon’s infamous “Enemies List.” According to Blumenthal, the Fritcheys hosted a party “with the usual suspects” for Carter when he arrived in DC, but the president-elect “never responded” to the invitation. Blumenthal sees this as evidence of a decline in interest in “what Georgetown thought” over the course of the 1970s; it can also be read as a sign of Carter’s embrace of his “Washington outsider” image.

En route to the party, we get another glimpse of both Lacey and Dick’s deep connection, and Dick’s occasional insecurities about it. He again worries that he won’t be able to keep Lacey’s attention in DC: after all, who, at a gathering of political luminaries, would “want to talk with an elderly ornithologist?” Lacey again eases Dick’s mind, reminding him of what they share. “In thirty-five years,” she tells him, she had never attended a function at which Dick “wasn’t the most fascinating person” in attendance.

But Dick’s fears come true: the butler closes the door in his face.

Dick spends the rest of the evening in the den, watching TV and talking about “the merits of Ivy League vs. Big Ten football” with former University of Michigan football star (Go Blue!!!) and outgoing President of the United States, Gerald Ford.

Dick’s account of his rec-room hangout with Ford allows GBT to synthesize character-building with political caricature: as he underlines Dick’s social awkwardness, he gently spoofs Ford’s workaday public image. The New York Times obituary for the former president described him as “the nice guy down the street … more fundamental than flashy”; the kind of guy who might prefer to retreat to the den to watch a football game during a dinner party. There’s also a deep literary reference underpinning the joke’s set-up. Dick talking football with Ford brings to mind another moment in which a president’s love of football led to an unexpected encounter: Hunter Thompson’s fabled 1968 midnight ride through New Hampshire with Richard Nixon, where the unlikely pair, both huge football fans, discussed Green Bay’s recent Super Bowl win. Trudeau never took the opportunity to put Nixon and Duke, HST’s comics-page incarnation, into the same strip. Here, instead of the mad Gonzo energy such a moment would have created, we get something that runs a little deeper – a thoughtful, friendly encounter between two decent men.

That sense of gentleness, which permeated many of the strips featuring Lacey and Dick, didn’t keep Trudeau from using Dick’s voice to dish out a more biting type of political commentary. As GBT took a good-natured jab at the outgoing president’s unassuming character, he also sharpened his knife for the incoming administration. Lacey tells Dick that she’s “keen” to attend the event because “the entire Carter cabinet will probably be there”; as an incoming representative, she wants to “size up the people in charge.” Dick remains unimpressed: “The Carter cabinet,” he replies, “is the most bizarre collection of cronies, retreads and tokens ever assembled.”

Dick’s evaluation of the makeup of Carter’s cabinet reveals the cynicism underlying Carter’s embrace of an “outsider” status while pursuing Establishment politics-as-normal. Carter’s campaign emphasized his rural, Southern roots: grassroots workers called themselves the “Peanut Brigade”; his team of core advisors was nicknamed the “Georgia mafia” by Washington insiders. Yet as his team moved from campaigning to governing, many of the “bright new faces” who helped get Carter into the White House found themselves on the outside looking in as key positions went to the very people who were supposed to be excluded because of their Establishment credentials. On the campaign trail, Carter’s campaign manager, Hamilton Jordan, promised Playboy’s Robert Scheer that a future Carter administration would “run by people you have never heard of,” pledging to quit if Carter chose Establishment figures like Zbignew Brzezinsky (Ivy League professor, member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the Bilderberg Group, co-founder of the Trilateral Commission) as National Security Advisor or Cyrus Vance (former Secretary of the Army, Deputy Secretary of Defense, advisor to Lyndon Johnson) as Secretary of State.

Both men ended up in those exact positions; Jordan reneged on his promise to quit and became Carter’s chief of staff.

As he dismisses the “cronies and retreads” whose nominations undermined Carter’s “outsider” political identity, Dick dismisses the more inclusive hires the Carter team made as “tokens.” It’s a fair point: Carter’s cabinet was overwhelmingly White and male, the only exceptions being Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Patricia Roberts Harris (the first African-American woman to serve in the Cabinet), Secretary of Education Shirley Hufstedler, and the first Black United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Andrew Young.

Both of these arcs are topically dense, featuring cutting political satire, observations about DC society life, a gentle take-down of a cultural institution with elitist pretensions and other bits of commentary. What keeps this topical density from bogging down the narrative flow is that the heavy lifting is done by a pair of endearing characters who, still relatively new, were revealing themselves to readers as compelling, complex people.

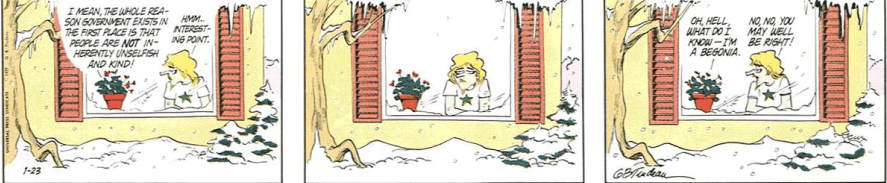

Trudeau ended his look at the transition with a Sunday strip that brings us full circle to the Carter campaign’s early messaging, this time voiced by one of Zonker’s potted plant buddies, Nemo. Reflecting on Carter’s inauguration, Nemo tells Zonker that, while he’s “all for him,” he worries that Carter may try to actually “make good on his pledge to make the government as nice as the American people,” a reference to a line from Carter’s stump speech that Trudeau had built into a number of strips over the previous year. “The whole reason government exists in the first place,” Nemo observes, “is that people are not inherently unselfish and kind.”

“Oh, hell,” concludes Nemo. “What do I know – I’m a begonia.”

A houseplant’s take on Carter’s political naivete; Dick’s observations about Carter’s cynicism. As Carter, Lacey and Dick went to Washington, Trudeau was laying the groundwork for how he would address a new challenge facing him after more than six years of skewering Republican presidents: sharpening his pen to wield against a president from the other side.

Stay tuned.

Hi Paul, the “covering Ryan O’Neal” link in paragraph 3 is broken – it repeats the target URL twice, ending up with something the GoComics web server can’t interpret. Apart from that, great work as usual!

LikeLike

Fixed. Thanks for the heads-up, and thanks for reading!

LikeLike

Just noticed that Nemo is a scarlet begonia.😁

LikeLike

Good god.

LikeLike

😁

LikeLike