Recently, I wrote about how Garry Trudeau felt frustrated with his writing about the 1976 elections, much of which focused not on the presidential race, but on Ginny Slade’s Congressional campaign. That story had a lot of moving parts, some new, many of which became permanent fixtures of the strip: the introduction of Lacey and Dick Davenport as regular characters; the start of Rick and Joanie’s relationship; and GBT’s explorations of the music business through the eyes of Jimmy Thudpucker (who did a benefit single and concert for the campaign). Looking back, Trudeau criticized the arc, saying that its busy-ness forced him to put out material before it was fully developed. My own reading is that any shortcomings in terms of character and plot development came from Trudeau trying to push his work into new ground, synthesizing political satire with more compelling, personal storytelling.

Looking back in 1986, a decade after the fact, Trudeau pointed to a sequence that ran a few weeks after the 1976 election as a sign that he’d found his feet after that challenging period: the story of B.J. Eddy, the “Head Tulip” at the White House, who was fired by the Carter transition team after eight years of public service. “I finished that week,” Trudeau remembers, “and I knew I was back on track.”

The story of Ginny’s campaign combined the kind of political satire that GBT had honed through his strips about Watergate and Vietnam (earning him the 1975 Pulitzer for political cartooning) and his experience as a member of the White House press corps on President Gerald Ford’s state visit to China with a new attention to character development and emotional nuance. From an implicit sense of the kind of connection that only exists between people who spend a lifetime together (Dick and Lacey) through the joys and fears that come with falling in love with someone new (…when Joanie wakes up with Rick for the first time, her face conveys that perfect blend of happiness and uncertainty that underpins new love), by the end of 1976, GBT was deeply digging into his characters in new ways.

Ginny’s story allowed GBT to grow as a storyteller; the B.J. Eddy arc points to another critical dimension of Trudeau’s work, something I discussed in a recent post looking at some of Trudeau’s reflections on cartooning as social critique. In his preface to the first Doonesbury anthology, Trudeau describes “the indispensable function of the of the cartoonist in society”: to help readers see the world as children do, allowing us to engage, however briefly, with the “nonordinary realities” typically hidden from our jaded eyes, thereby revealing truths hidden from us in our arbitrary consensus reality. Looking at the B.J. Eddy strips after reading Trudeau’s insights into the transcendent possibilities of cartooning, I better understand his rationale for seeing them as a return to form. Let’s dive into them and see why.

***

Zonker is the most prominent of a few Doonesbury regulars (think of Bernie’s dimension-spanning techno-scientific endeavors or Duke’s chemically-induced nightmares) who have varying degrees of access to those nonordinary realities usually closed off to most of us. Zonker’s relationship with his houseplants is a great example of Trudeau developing sustained storylines that explored the non-consensus realities Zonker frequented.

Zonker began talking with his houseplants in October 1974, about a year after Jerry Baker wrote a popular gardening book titled Talk to Your Plants and Other Gardening Know-How I Learned from Grandma Putt. The early strips featuring Zonker’s plants brought a taste of the psychedelic weirdness of the underground comix to mainstream funny pages. These strips are a lot of fun: one running gag centers on Mike’s alleged cruelty when he’s plant-sitting for Zonker; in another arc, Zonker takes Patty the Potted Palm to a “houseplant convention” which features a photosynthesis workshop and a screening of “an award-winning documentary on one day in the life of the sun” that includes “very controversial” footage of dawn. That said, while there’s a goofy sense of whimsy that runs through these strips, Trudeau draws no real connection between Zonker’s plants’ world and our own. Like virtually all of Zonker’s psychedelic interludes, the potted plants stories are pure escapism.

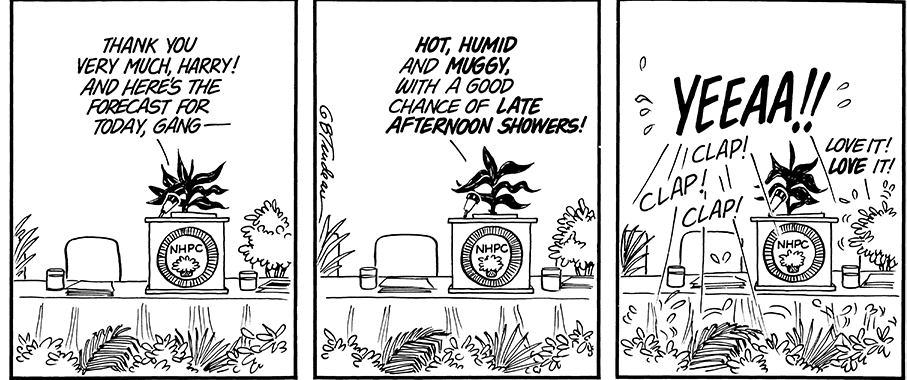

The convention arc hints at the possibility of doing something in a more topical vein with the trope of talking houseplants, but doesn’t deliver. The event’s keynote speaker was B.J. Eddy, the “Head Tulip from the White House lawn.” But B.J.’s only appearance in that sequence goes no deeper than a throwaway joke about banal convention speeches. Like the rest of the arc, it’s serviceably funny (though not as clever as the preceding installment, which sees attendees cheering the daily weather forecast – “Hot, humid and muggy, with a chance of late afternoon showers!”) but it doesn’t let Trudeau say much about affairs away from the comics page.

After Ginny’s campaign wrapped up, however, Trudeau ran a week-long arc that’s a prime example of how a story that unfolds in a nonordinary reality can allow for commentary on stories unfolding in other parts of the newspaper.

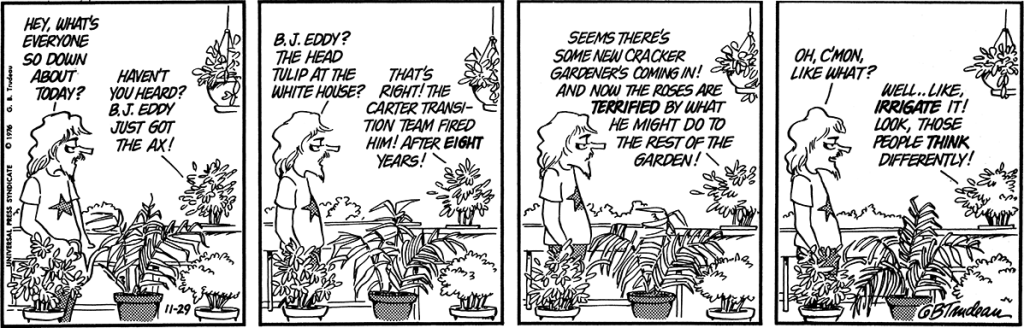

On 29 November 1976, Zonker dropped in on his houseplants, who were upset about a recent bit of news: Jimmy Carter’s transition team had fired B.J. Eddy, a “perennial’s perennial” with a reputation as “an aggressive, early bloomer,” from his role as White House lawn’s Head Tulip.

While B.J.’s first appearance contained no real political insights, in this arc Trudeau digs deeper into the political dynamics surrounding his termination. The changeover from the outgoing Ford administration to the Carter presidency has been described as “the first systematic exercise in transition planning,” marking a moment when the process of changing presidents evolved from one that typically unfolded “over a few months, involving a small number of people” to one that “takes years and includes thousands of career civil servants as well as political professionals.” Letting go of B.J. represented an instance of candidate Carter’s promise “to bring fresh faces into the government”; he got the ax as a symbolic expression of the incoming administration’s desire to present itself as a clean break from the overlapping social and political crises of the previous administrations.

Given B.J.’s history as a holdover from the Nixon years, Trudeau can’t resist taking a shot at the disgraced former president as a final symbolic link to his time in the White House is severed. One report features an interview with a White House gardener recalling how B.J. had, during a “particularly depressing period” of Nixon’s presidency, “arranged for a row of jonquils outside the Oval Office to burst into bloom in the middle of January.”

“Mr. Nixon,” the gardener reveals, “ordered them cut down, of course.”

Alongside a dig at the last Republican elected to the White House, GBT takes a poke at some of the class and racial dynamics surrounding Carter’s election. Nancy Isenberg, in White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, examines Carter’s – and America’s – ambivalent relationship with rural Southern culture in the 1970s. While American men adopted redneck cultural tropes like stock-car racing and cowboy hats to express a more traditional “authentic” masculinity, fears of Southerners as morally degenerate “hillbillies” found expression in popular outlets like Deliverance. When he ran for governor of Georgia in 1970, Isenberg observes, Carter leaned hard into his rural identity as a way to set himself apart from the political Establishment. In 1976, Carter took a more nuanced approach to his self-presentation, equal parts good-ol’-boy peanut farmer in an Allman Brothers t-shirt and straight-laced policy wonk. Carter boasted that Andrew Young, an advisor on racial relations and the first African-American ambassador to the United Nations jokingly called him “poor white trash made good.” And yet, as Isenberg notes, in some ways he never “made good”: one genealogist “invoked eugenic thinking when he claimed that the Carter family had produced ‘intelligent to brilliant’ people,” and concluded that “Jimmy’s brother Billy had acquired his less fine attributes” from one of the “less successful branches” of the Carter family.

Zonkers’ plants echo those anxieties about Carter’s background as they describe the circumstances surrounding B.J’s termination. One blames B.J’s fate on “some new cracker gardener” taking over White House landscaping duties, and there were rumors that the White House roses were “terrified by what he might do to the rest of the garden.” Zonker is doubtful: “Oh, c’mon. Like what?”

“Well … like irrigate it,” comes the reply. Carter’s background in peanut farming marks him as someone to be feared and loathed, a definite “other” for Zonker’s pals, and some of the American public: “Look, those people think differently.”

As he draws on lingering resentment against Nixon and mocks bourgeois anxieties about the incoming Carter administration, GBT also finds room to engage with a couple of contemporary stories unfolding further from the confines of the White House garden.

The first is the kind of obscure reference that must drive comic-strip editors mad. In the penultimate strip of the sequence, CBS News anchor Eric Severeid describes B.J. as having “an ebullience that would have delighted Alexander Calder.” That’s a pretty deep cut for the funny pages, but given that Garry was just a couple of years past earning his MFA from Yale, it was an apt one: Calder was an American sculptor best known for large-scale public art and for kinetic sculptures powered first by motor and then by wind. Calder died on 11 November 1976 – three weeks before B.J.’s story ran.

The arc’s final strip brings us to the intersection of global politics and a landmark development in American broadcast journalism. On 4 October 1976, Barbara Walters of ABC News made her debut as the first woman to co-host a network evening newscast, a major media event that was covered more widely than any of the stories reported by ABC News that evening. Walters’s first night on the job featured an exclusive interview she’d conducted with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. On the comics page, when Walters speaks with B.J., he greets her the same way Sadat had in that historic broadcast: “Only for you, Barbara, would I do this exclusive interview!”

One of Doonesbury’s most common tropes involves a given character watching the news across four mostly-static panels, their subtle reactions underlining whatever weirdness emanates from the screen. By making Zonker and his leafy buddies the audience, Trudeau signals that the world depicted on screen is going to be even more bizarre than normal. But as GBT takes us along with Zonker as he explores events unfolding beyond the boundaries of consensus reality, he consistently signals events in the “real” world in ways that, at least for as long that it takes to read a comic strip, unsettle our sense of reality – and maybe better see things as they are.

***

Generally speaking, I don’t want to get too deeply into the question of how any given Doonesbury moment reflects Garry Trudeau’s personal life. My interest is less in the creator’s biography than it is in how his strip reflects a particular take on broadly-shared experiences. That said, the strips from the week before news of B.J.’s termination became public clearly point to some of the insecurities GBT had been feeling about his work as the 1976 election cycle played out in Doonesbury.

In the days before B.J. got the ax, Zonker returned to the Walden College football team after taking most of the year off to work on Ginny’s campaign. While he encountered some eligibility issues after failing to attend classes for the first two months of the semester, Zonker announced his comeback to the 0-for-7 team with glee: “He’s back! In fighting trim and ready to go! …We can all breathe easy now! El Season is saved!”

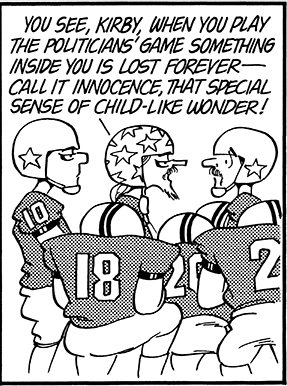

Zonker’s joy at being back on the field is tempered, however, by his worries about what his time in the cynical world of electoral politics may have done to him. “It’s exciting and glamorous,” he tells his teammate Kirby, “but that’s only part of the story”:

“You see, Kirby, when you play the politicians’ game something inside you is lost forever – call it innocence, that special sense of child-like wonder.”

Zonker’s realization about the stakes of spending too long a time in the trenches sets the stage for the following Monday’s announcement about B.J. Eddy, a moment that makes it clear that Zonker’s “special sense of child-like wonder” had survived his encounter with “the politics biz.”

And so had Garry Trudeau’s. Quite self-consciously, Trudeau puts us at the intersection of his musings about the transcendent potential of cartooning, and his sense that he had lost and then regained something after the experience of covering Ginny’s campaign.

Next up in my look at Doonesbury in the Carter years: the art of political symbolism and the perils of talking to the people.

Stay tuned.

3 thoughts on “BJ Eddy Gets the Ax: Doonesbury in the Carter Years, Part VI”