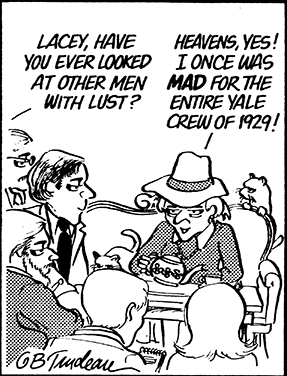

On 13 October 1976, Lacey Davenport, a “little old lady” the “Republicans [were] running” in a California Congressional contest, gave an informal press conference over tea at her tastefully-appointed home. A reporter asked a follow-up question to an inquiry about her relationship with her husband, Dick: “Lacey, have you ever looked at other men with lust?”

Lacey answered in the affirmative, smiling as she recalled being “MAD for the entire Yale crew of 1929.”

The joke was a reference to Jimmy Carter’s recent Playboy interview, in which the Democratic candidate for the Presidency discussed, among other things, the difficulties in living to the “almost impossible standards [Christ] set for us”:

Christ said: “I tell you that anyone who looks on a woman with lust has already committed adultery.”

I’ve looked on a lot of women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times. This is something that God recognizes that I will do – and I have done it –and God forgives me for it.

The point of Carter’s confession was that he needed to be as forgiving of the sins of others as God was of his:

That doesn’t mean I condemn someone who not only looks on a woman with lust but who leaves his wife and shacks up with someone out of wedlock.

This is Part III of my look at Doonesbury in the Carter years. We’ve seen how the 1976 election unfolded as America confronted the painful legacies of the social and political tumult that had unfolded over the previous decade or so while looking to an uncertain future as the economic and political foundations of the country appeared shaky. Hunter Thompson’s essay about Carter’s Law Day address and the interview with Playboy’s Robert Scheer examined how Carter navigated the tensions between his seemingly-incongruous personas: which was the “real” Jimmy Carter, the pious Southern White patrician or the progressive Bob Dylan fan? The answer was “both.” The next couple of posts are going to examine how Garry Trudeau covered the 1976 campaign, focusing on how some of the themes that emerged from the Thompson and Playboy pieces were reflected on the comics page. This post focuses on Carter’s campaign rhetoric during the primary season, as he tried to frame himself as a political outsider with a grand vision for restoring national trust following years of crises, but often became mired in policy specifics, leading to repeated charges that he was an inveterate flip-flopper. I’ll also talk about a reference that has stumped me ever since I first read it decades ago.

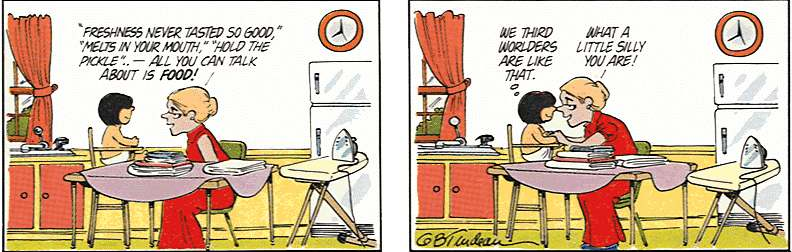

The first mention of Carter in a Doonesbury strip I found was from May 1976, in an arc featuring Kim Rosenthal (later Kim Doonesbury) and her adoptive father, Frank. Kim, the last orphaned refugee to leave Vietnam before the end of the war, learned to speak by repeating what she heard on television. Most of her early attempts at self-expression involved parrotting advertising slogans for fast-food chains – a reasonable obsession for “Third Worlders” like her – but during the 1976 primaries, Kim found a new voice to emulate, one that made her “the only Vietnamese orphan in L.A. with a Georgian accent.”

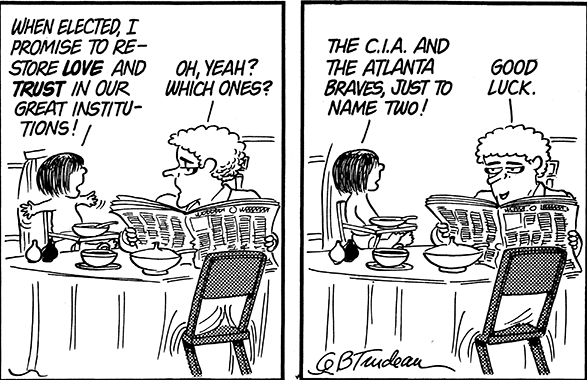

Kim’s fondness for the Burger King ads that inspired her first words was rooted in her traumatic past; her attraction to Carter’s message, perhaps, reflected a central theme driving Carter’s campaign, a promise of renewed faith in a country emerging from overlapping traumas. Kim echoes Carter’s self-presentation as a political outsider “untainted” by Washington politics and his promises to restore “LOVE and TRUST in our great institutions,” notably the Atlanta Braves (then on their way to a last-place finish in their division following a similarly-disastrous 1975 season) and the CIA (the target of Senate and House investigations of misdeeds ranging from COINTELPRO and MKULTRA to assassinations and attempted assassinations of foreign leaders). Frank’s bemused response, reflecting a weary post-Watergate cynicism about the likelihood of real change : “Good luck.”

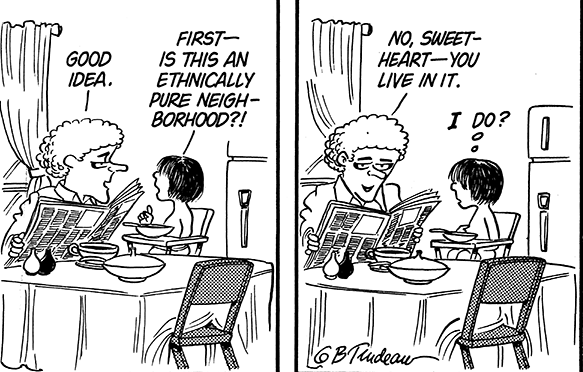

Kim is particularly interested in one of the campaign’s hot-button issues, the use of government power to redress structural racism in contexts like housing. Her musings revealed some of the ambiguity – and clumsiness – at the heart of the Carter campaign when it came to articulating policy specifics. Like Carter, Kim seemed more comfortable discussing lofty values than the finer details of policy-making.

Carter was widely criticized for his flip-flopping, particularly when it came to questions having to do with race. As Scheer noted, Carter had difficulty reconciling his essentially progressive views on race with his personal history as an elite White patrician during the South’s history of legalized white supremacy. Carter’s personal, decidedly incomplete, reckoning with that tension reflected a larger cultural dynamic: for instance, the campaign unfolded as Alex Haley’s Roots was becoming a bestseller and bringing renewed attention to America’s racist history. While he was generally on the right side of things, Scheer argued, the complexities of American race relations made it inevitable that Carter would have made moral compromises because of his social position. On a more practical level, Carter’s progressive values existed in tension with his political need to satisfy competing constituencies. He understood that the government had a role to play in addressing the effects of structural racism; he also knew that a heavy-handed approach would alienate the White suburbanites that were a core to his election hopes. Carter supported federal and state open housing laws (that year, Congress modified the Equal Credit Opportunity Act to outlaw racial discrimination in regards to mortgage and other loans) and the use of legal mechanisms to ensure fair access to housing built with federal funds. At the same time, he countered criticism of his belief in the positive role the state could play in race relations by maintaining that he would not favor the “[arbitrary use of] Federal force to move people of a different ethnic background into a neighborhood just to change its character,” a policy that literally nobody was proposing, but was a popular conservative bugbear.

Kim’s Carter impersonation was shaped by a recent gaffe the candidate had committed while discussing that non-existent policy proposal: as he assured suburban voters that his plans to rectify the effects of America’s history of institutional racism did not extend to what would literally amount to ethnic cleansing, he used terms including “ethnically pure,” “black intrusion,” and “alien groups” to talk about American citizens and the neighborhoods in which they lived. Andrew Young, the future US ambassador to the UN and Carter’s chief advisor on racial issues, called the incident a “disaster”that had the potential to end the campaign, but Carter apologized and recovered his momentum.

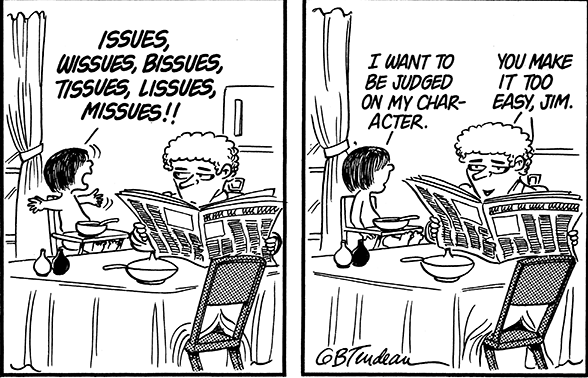

The scene is the Rosenthal breakfast table: Kim-as-Carter wants to talk housing, but first asks if she’s in an “ethnically pure neighborhood,” (she’s taken aback to discover that her very presence means that it isn’t.). In a later strip, she doubles down on her pledge to “keep big government out of our ethnically pure neighborhoods” and “put discrimination back in the hands of local authorities.” Like Carter, Kim is frustrated by a focus on complex “issues, wissues bissues lissues missues”; she would rather be “judged on [her] character.” Much like the candidate who seemed more comfortable dealing in lofty ideals than challenging policy specifics, Kim remained confident that “love and trust will keep out the alien groups.”

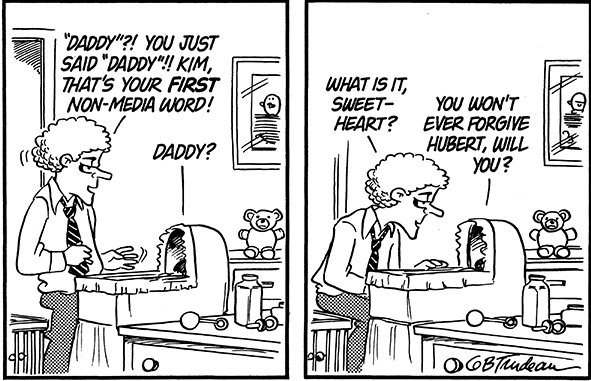

Baby Kim is one of my favorite occasional characters; I love how she balances political/cultural commentary and whimsy. Her attraction to Carter, I think, reflects the same dynamic beneath her fascination with McDonald’s commercials: a naive faith in America as a land of plenty, and of hope for the future. But as much as I have always loved her appearance as Jimmy Carter, the last strip in the arc frustrates the hell out of me, and has done for years. Frank is putting her to bed (“even front-runners have to get some sleep!”) and she says her “first non-media word”: “Daddy.” Frank’s joy is short-lived as his infant daughter slips back into her political incarnation: “You won’t ever forgive Hubert, will you?” About a month later, the line reappears: two reporters sit in a newsroom, contemplating a bet on an upcoming primary: “Twenty bucks says Humphrey takes it,” says one..” “Actually, I’ve forgiven him,” his colleague responds.

I’ve never been able to figure out exactly what GBT is referring to here. Obviously, the joke is a reference to Hubert Humphrey, LBJ’s VP and the candidate who lost to Nixon in 1968. Humphrey’s continued support for the war in Vietnam cost him the election, as voters fell for Nixon’s promise of “peace with honor”; it ultimately led to his alienation from liberal Democrats, even as he had, in earlier days, been greatly admired for his dedication to the cause of civil rights. While there was some tension between his camp and Humphrey’s during the primary campaign, Carter generally spoke fondly of Humphrey, and it makes sense that he would, if only in the name of party unity, urge the faithful to forgive a man with a long record of public service.

And yet, I can find no reference to Carter talking about forgiveness and Humphrey during the campaign. I found one Twitter user who mentioned a similar quote from Carter, but when I reached out to him he couldn’t remember anything more specific.

Obviously, Carter said something that had enough of an impact on the public discourse to warrant GBT writing two separate jokes a month apart, but this one has me stumped. Reach out with any hints you might have.

Next time out, we meet the man himself.

2 thoughts on ““Is This an Ethnically-Pure Neighborhood?”: Jimmy Carter on the Campaign Trail”