Vietnam remains America’s most divisive foreign war and the divides it caused shaped American politics and culture for decades after the fall of Saigon. Alongside questions about its rationale for getting involved in a senseless endeavour that was doomed to fail and its conduct during the war, a key question that America had to confront in the years and decades following the war was that of the thousands of men who defied their country by resisting conscription, either by taking advantage of various sorts of privilege that allowed them to legally avoid the draft, or by leaving their loved ones behind, perhaps forever, to seek asylum abroad, notably in Canada. In a country where the president is also the Commander-in-Chief of the armed services, the question of what a presidential candidate did during Vietnam looms large. All three presidents who are of Garry Trudeau’s generation – Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump – have faced criticism about why they didn’t serve in Vietnam and how they managed to avoid it.

Surprisingly, for an issue that was at the front of the minds of many American men who were of an age with Zonker, Mike and Mark, the draft did not feature prominently in the early Doonesbury strips. B.D. volunteered for combat, and the only instance of someone receiving the dreaded “Greetings” notice features a minor character who was never seen again. Trudeau’s only substantial engagement with the draft and those who refused to submit to it came the year after the Nixon administration stopped drafting young men to fight in Vietnam.

On 16 September 1974, my fellow Wolverine, President Gerald Ford, proclaimed a conditional amnesty for draft dodgers and men who had deserted the armed forces during the Vietnam war. Ford justified the amnesty on the grounds that “reconciliation calls for an act of mercy to bind the nation’s wounds and to heal the scars of divisiveness.” A month after Ford signed the proclamation, Trudeau wrote about two amnestied draft dodgers giving a press conference to share their reactions to Ford’s policy. The arc is partly an attack on the contrast between the conditions imposed on war resistors looking to rejoin American society and those granted to a man who had done as much to undo American democracy as anyone else up to that point in the country’s history, and partly a tribute to the country where many draft dodgers ended up.

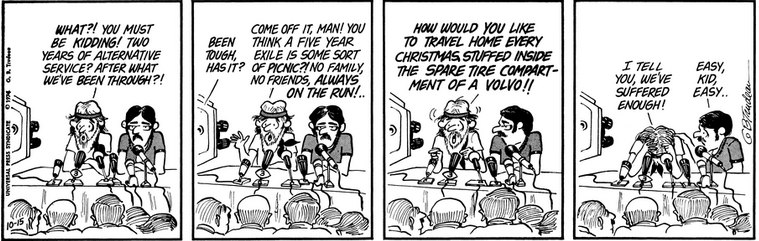

The two draft dodgers begin their presser by expressing their pleasure at the terms that Ford had attached to their pardon: “a $60,000 pension, $400,000 transition expenses, and $12,000 for a valet.” Their pleasure turns to disappointment when a reporter informs them that they had in fact confused the terms of the draft amnesty (which actually imposed a two-year-long stint of alternative national service) for the benefits that were part of Ford’s recent pardon of disgraced former president Richard Nixon. Nixon may have gotten off scot-free, but our heroes have to do “two years of alternative service” after spending five years in exile, coming home for Christmas “stuffed inside the spare tire compartment of a Volvo.” The juxtaposition of the contrasting resolution to two of the principal political stories of the previous decade, the Vietnam war and the corruption of the Nixon administration, is stark. In America, some people, because of their status, are not really expected to take personal responsibility for their crimes; those who make important sacrifices for the cause of peace and justice cannot get the same kind of official forgiveness. (In 1977, Jimmy Carter issued an unconditional amnesty for those who had evaded the draft; Carter’s amnesty did not extend to deserters.)

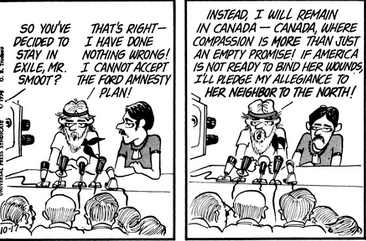

The rest of the arc is a tribute to the nation that gave asylum to the men who chose to leave their country rather than fight an unjust war. Canada, the amnestied dodgers say, is a country “where compassion is more than just an empty promise,” and a land where “government works.” After all, they say, Garry Trudeau’s distant cousin, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, didn’t deal with campus unrest with “the whole repression trip”: instead he “married a co-ed,” namely Margaret Kemper-Trudeau, the much younger wife of then-PM Pierre and mother of current PM Justin Trudeau. The two also note their approval of Canada’s role during the Chilean coup the previous year, making an oblique reference to Canada providing a haven to refugees fleeing the abuses of the Pinochet regime following the fall of the democratically-elected Salvador Allende government.

While these claims about Canadian tolerance and generosity are central to how Canada presents itself to the world, they hide important truths. First, the duo are overselling Canadian tolerance of radical movements during the Vietnam era. When Black activists took over the computer centre at Montreal’s Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University) in 1969, the police responded with brutal violence, forcing protestors to lie in broken glass, holding a cocked pistol to the head of one Black man, and making vile sexual and racist comments to the people they arrested. And while Canada did admit an important number of Chilean refugees following the events of 1973, the country was solid in its support of the Pinochet regime and did little to criticize Pinochet’s incarceration, torture, and murder of Chileans whom Canada’s own ambassador to Chile characterized as “the riffraff of the Latin American Left to whom Allende gave asylum.”

Canada may not be the virtuous country that the draft-dodgers – and most Canadians – believe it to be. But the fact remains that our two heroes and many more like them were able to escape serving in an unjust war by crossing the border. Canada not only provided refuge for American men fleeing the draft, it gave many of them a permanent home. The Canadian government estimates that some 40,000 draft dodgers came to Canada; most of them stayed, becoming, according to one government report, the “largest, best-educated group this country ever received.” Prominent Canadians who came here to escape the draft include the science fiction writer William Gibson and sportswriter Jack Todd, who settled in Canada after deserting from the U.S. army. Todd’s The Taste of Metal is a compelling and moving memoir about the experience of political exile in the Vietnam era.

Like Gibson, Todd and so many others, the two amnestied draft-dodgers decided to stay in Canada, pledging their allegiance to America’s “neighbour to the north, as opposed to a country that is “not ready to bind her wounds.” Though while our heroes are going “…back to the tall whisperin’ pines and hot maple syrup, red-coated mounties perched high in their stirrups, hard rubber hockey pucks shot from the wing” and a few more of their favourite things, those men who served in the war, and the country that sent them there, will have to bind their wounds. That’s for next time.

Peace.

One thought on “Vietnam, the Aftermath: Part II, “Stuffed inside the Spare Tire Compartment of a Volvo.” The Draft Dodgers.”